REDD+, So Long as “the Poor Sell Cheap”

There are a number of reasons why REDD+ forest carbon has received such widespread attention. Perhaps the least romantic reason…

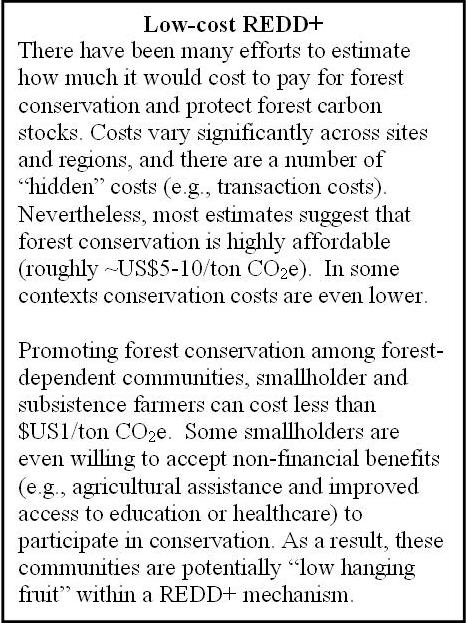

Low-cost REDD+REDD+ is cheap (at least on the surface).

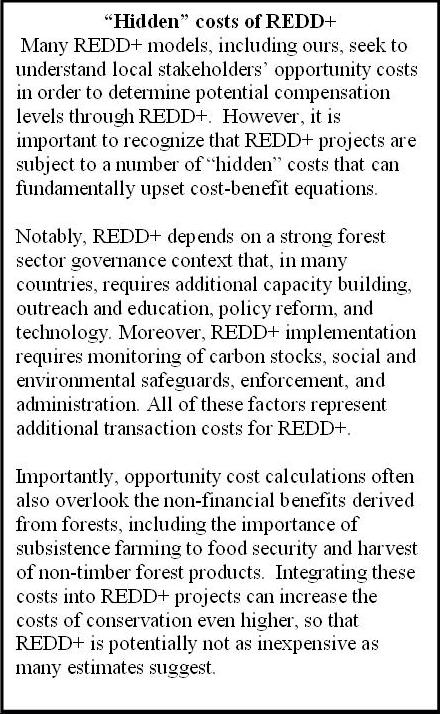

There are strong economic arguments for implementing REDD+. Forest conservation and sustainable management are potentially large-scale, arguably low-cost strategies for reducing greenhouse gases to mitigate climate change. Low agricultural yields, geographic isolation and widespread poverty in many tropical developing countries often mean that small incentives can motivate governments and individual landholders to protect land for conservation.

Financing a large-scale REDD+ mechanism may depend on these comparatively low costs, driven by efforts to find lowest-cost emissions reductions. This potentially places subsistence farmers, smallholders, and community forestry groups at the center of REDD+ initiatives, particularly where they are willing to “sell cheap.”

But the poor won’t sell cheap forever.

In a recent study, my co-authors and I considered the costs of REDD+ in the context of increasing opportunity costs among small-scale and subsistence farmers. We used the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) as an example for considering how costs among smallholder farmers can change over time. The trends we uncovered are particularly relevant in the context of the current Asian agricultural boom.

Our analysis confirmed that many small holders in the DRC would potentially be willing to participate in conservation given very small incentives. Indeed, many subsistence farmers in the DRC suffer from low farm yields, low incomes, and high food insecurity, similar to smallholder and subsistence farmers across much of the developing tropics.

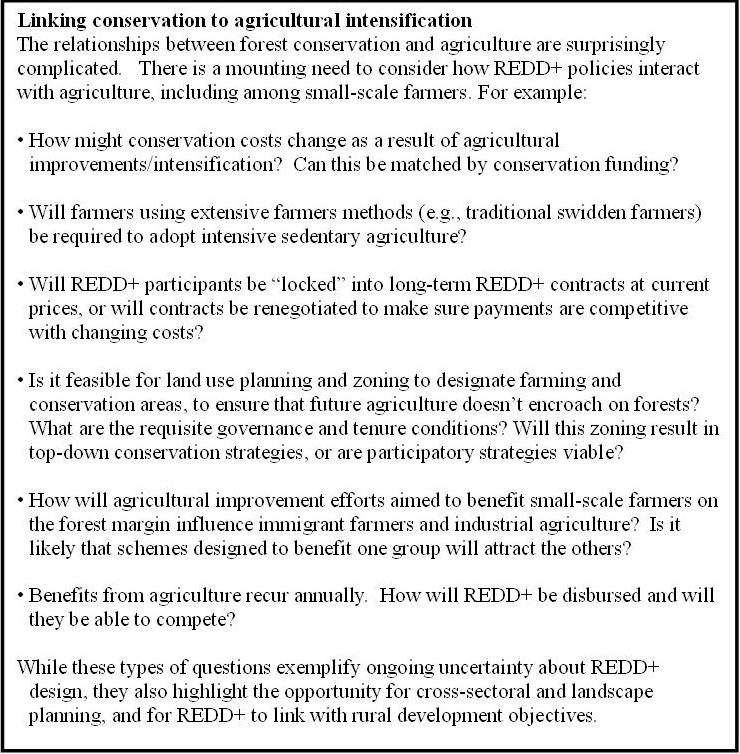

At the same time, however, many smallholder farming communities in the DRC are being targeted for agricultural support. As in many other developing countries, farm yields could radically improve with the introduction of new disease-resistant plant varieties, increased fertilizer use, and improved transportation and market access. This support could bring dramatic, necessary benefits to local farmers.

However, increasing farm yields would also increase the costs of conservation.

Farmers who were once willing to protect forests for a pittance could begin to demand more for their conservation actions. Small-scale farmers might also be displaced by immigrants and larger commercial agriculture as farming becomes more lucrative in areas that were previously less productive and/or isolated from markets.

Based on our scenarios of agricultural improvements among small farmers in DRC, we modeled that conservation costs could increase 8-20 fold within 30 years. While these were hypothetical scenarios, they illustrated how, as farmers’ costs increase, so too must REDD+ payments.

While our focus was on the Congo Basin, the findings are easily reflected and magnified in the Asian context. Rapid agricultural expansion and the recent boom in high-value coffee, oil palm, and rubber production mean that farmers’ opportunity costs in Asia are already increasing.

Further intensification of these high-value crops could reflect even greater increases in the costs of conservation.

Conservation spending may have to dramatically increase to compete with future agriculture.

Many conservation groups are actively linking agricultural improvement programs to conservation policies. These are attractive because they promise win-win solutions for conservation and rural development, at least in the short-term. We suggest that these efforts may be overlooking the impacts of these policies on long-term conservation.

Will REDD+ still be attractive if costs increase in the future? Or will tropical developing countries and small-scale farmers only prove viable REDD+ and conservation partners while they sell cheap?

To read more about this research, please visit: