Who owns which forests? Investigating forest tenure in Asia

Local people have the least rights when it comes to forestland, says Julian Atkinson

As my RECOFTC colleague Yurdi Yasmi noted during the Asia–Pacific Forestry Week, ‘good’ forest governance requires managing multiple interests to achieve social justice. The last few decades have seen encouraging signs of progress in our region, as spaces have opened for engaging local communities and indigenous groups in forest management, particularly through national decentralization processes and the emergence of grassroots movements demanding social reforms. But how equitable, really, is the ‘playing field’ for local people in forest governance? What stake do they have in managing the forests on which they depend for livelihoods, subsistence and a way of life?

A recent study*, Forest Tenure in Asia: Status and Trends, provides a starting point to exploring these questions. Tenure security plays a strong role in the structure of incentives that motivate the protection, development or destruction of forests. Importantly, it can determine who benefits or loses in the competition for economic goods and environmental services provided by forest ecosystems.

Unsurprisingly, the study found that governments in almost every country in the region still retain administrative control over the majority of the national forest estate (the two big exceptions are China and Papua New Guinea). In most countries, the proportion of forestlands designated for use, or privately owned, by local communities and indigenous groups are minor. For example, in Indonesia only three million (2%) of the country’s 135 million hectares of classified forestland are legally non-state domain.

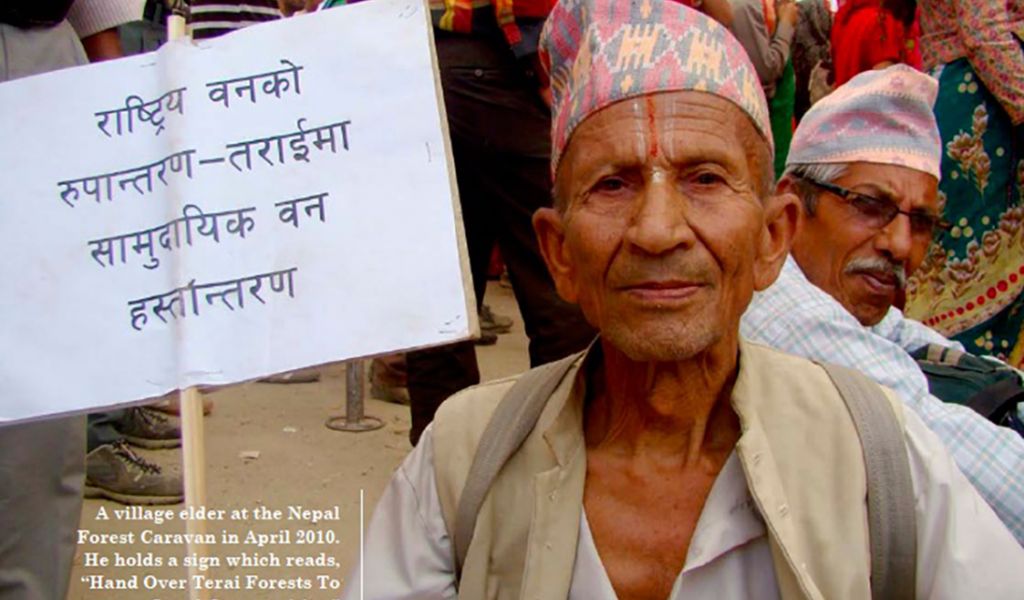

Taken at face value, the data collected in the study indicates slow regional progress in devolving tenure arrangements to local people. However, the lopsided numbers belie some reason for optimism. Governments in Cambodia, Indonesia and Vietnam only began legally recognizing community and household rights to forests in the last two decades, and are still in the process of piloting and developing statutory tenure arrangements for local people. Community forestry groups and federations in these countries are also just finding their feet and making their collective voices heard. Given time and support, there is good reason to believe forestry in these countries could mature along trajectories similar to China and Nepal, where laws for devolved forest management ensure local people are better positioned to exercise their rights.

This is not to say that major challenges and contradictions do not exist. While many governments have taken a guarded approach in devising the legal frameworks to support devolved community-based forestry, they continue to exercise quite liberal policies in granting companies rights to develop public forestlands. In both Cambodia and Indonesia, this has resulted in corporate forestland concessions covering over eight times more land area than forests held by local people. Companies also typically enjoy a wider range of rights and greater leeway to develop and utilize the natural resources within these concessions.

Conversely, rural communities and smallholders in many Asian countries are typically allocated rights over degraded and low-quality forestlands. For example, in Vietnam over 80% of forestlands allocated to collectives and households since 2002 are classified as plantations (as opposed to natural forests). This puts the onus on local people to rehabilitate forest areas and prolongs the length of time before they are able to realize the fruits of their labor. A tenure-devolution outlook that favors the corporate sector over local citizenry does not bode well for the future of forests, nor the achievement of social justice.

‘Good’ forest governance remains elusive in many parts of Asia and beyond. Proposed solutions appear increasingly complex as divergent agendas place ever greater demands on forestlands. If forestry is to yield successful outcomes for multiple interests at a global scale, those who are directly reliant on forests must be fully engaged in their governance. Resolving tenure-rights inequalities is a necessary first step.

You can read the full report at this link.

*This study was undertaken by RECOFTC with funding provided by the European Union and the governments of Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain and the United Kingdom through the European Union’s FLEGT Facility managed by the European Forest Institute. It builds on previous regional tenure studies undertaken by the Rights and Resources Initiative and the International Tropical Timber Organization.