Women join village leadership at an important moment in the evolution of Thai forestry policies

Ensuring policy reforms are gender-sensitive is made more difficult because gender-disaggregated data is missing 67 percent of the time in the decision-making processes in Southeast Asia.

This is why RECOFTC prioritizes research and activities to increase the representation and influence of women at all levels of decision-making in forestry in the Asia-Pacific region.

In 2020, RECOFTC conducted an assessment to examine the impacts of forest policies on women and local communities in Thailand. We collected data from Nan, Khon Kaen and Chanthaburi provinces through focus groups and in-depth interviews. The information will be shared with the communities, community forestry network members and policymakers to improve understanding of the differentiated impacts Thailand’s forestry policies will have on women.

The assessment comes at an opportune time. Communities across Thailand are mobilizing to form a citizen forests’ network, and we are observing positive shifts in community engagement across forest laws and policies.

In 2019, the Thai government amended the National Park Act to help reduce conflicts between authorities and forest communities living in national parks. The new Community Forestry Act of 2019 also opened the door for authorities to legally recognize community forests outside of protected areas. The government is now developing subordinate laws and policies to implement these Acts.

Women join village leadership

In November 2020, I joined my colleagues to visit Nam Mhaw, a village in the mountains of Doi Phu Kha National Park in Nan Province, Thailand, near the Lao border. This was the last site visited as part of the assessment.

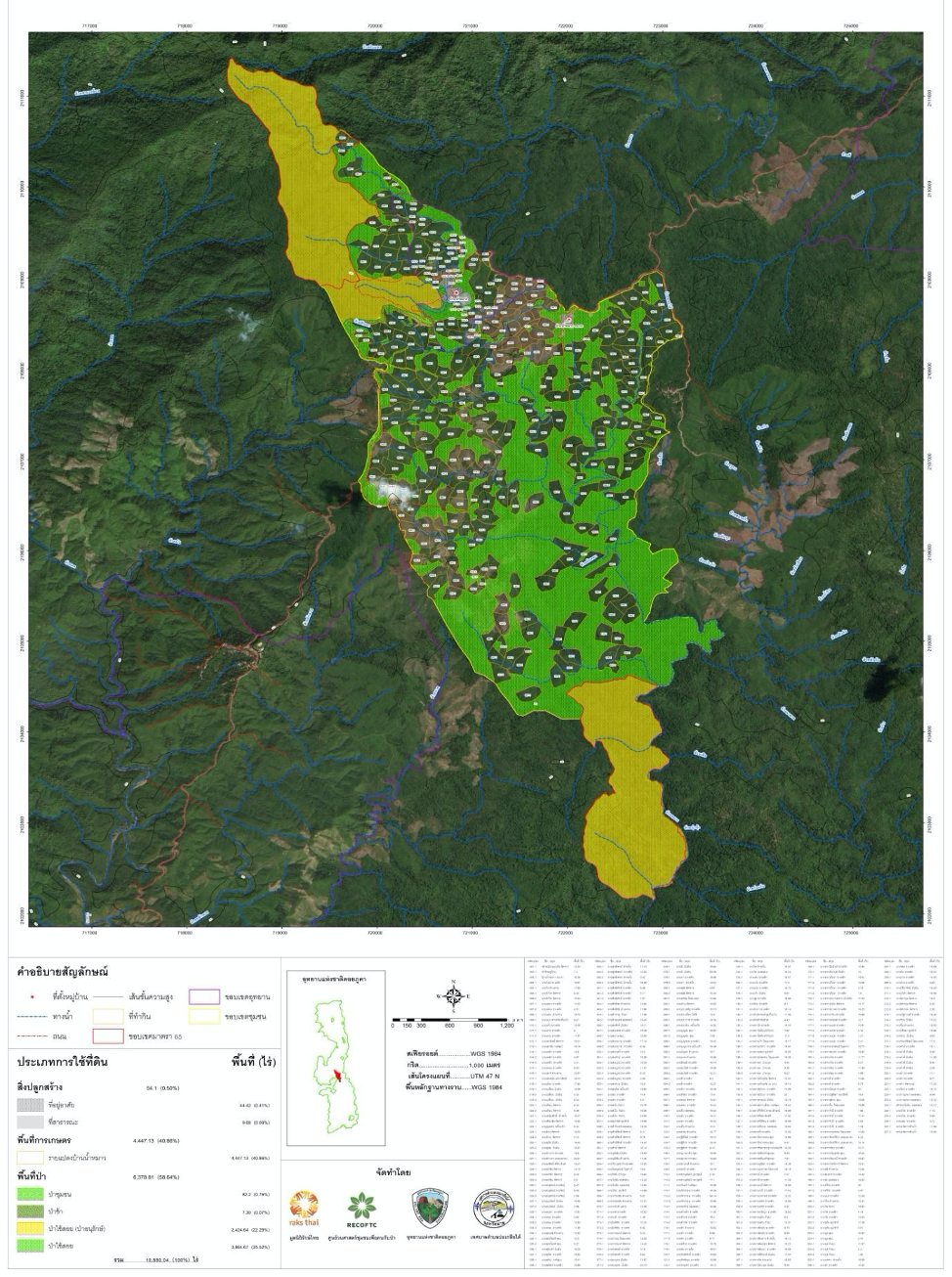

Nam Mhaw was historically a nomadic community. The villagers settled in this area almost 40 years ago because of its access to water and the abundant resources in the forest. When they settled, they began using an approach of communal forest management, which today supports the livelihoods of 393 villagers, 209 male and 184 female.

The villagers call their approach ‘community forestry,’ but the area that they manage and rely on is not legally recognized as a community forest under current Thai laws because it is inside a national park.

When they settled in the area, the Nam Mhaw community members set up a village committee to establish community rules and manage the communal forest. Of the 12 committee members only one is a woman.

During our visit to Nam Mhaw, we met two extraordinary female leaders, Somkuan Khalhek and Yupian Upajak. Khalhek was the first woman to run for an elected position in the community. Upajak became the first woman to join the village committee when the head of the village asked her to join the leadership team.

Meet Somkhuan Khalhek

Today, Khalhek runs the only convenience store in Nam Mhaw, but her entrepreneurial spirit emerged much earlier in life.

Nam Mhaw only offers schooling up to the sixth grade, but Khalhek went on to complete schooling up to ninth grade through distance learning. She finished the homework assignments and reading materials that were mailed to her, and she went to nearby schools to complete tests. Afterwards, she worked in Bangkok for many years before she returned home to Nam Mhaw, where she married and had two children.

She was only 26-years-old when she ran for an elected position in 2004.

Khalhek had to win votes from all villages in the sub-district to successfully become the representative for the sub-district administrative office.

After working in Bangkok and adjusting back to life in Nam Mhaw, she wanted to protect the local way of life from commercial exploitation. Her husband, family and the community’s support helped her to overcome her inner fears as she ran for the elected position.

During her tenure as the representative, she faced many pressures that her male peers did not. Among the challenges she experienced were those related to pregnancy and childcare duties.

Khalhek struggled juggling the responsibilities at the time. She served as the village representative for four years while also caring for her children, household and land.

The role required her to travel and attend regional meetings to represent the sub-district. This was a challenge because she can’t drive. When her husband was available, he would drive her to the meetings and trainings. It was also difficult being the only woman in the meeting rooms. In her culture, being alone with men other than family members is not encouraged. While Khalhek was proud of her work, she chose not to run again for the position at the end of her term. Her husband now holds the position in the village.

While women have served in different capacities in the village, only recently has another woman volunteered to take on a leadership role.

Meet Yupian Upajak

Upajak has worked for decades in farming, as well as construction and factories in Bangkok. The village leader asked her to join Nam Mhaw’s village committee in 2012.

Unlike Khalhek, she did not have to be elected to the position, but she knew it would be a big undertaking if she accepted the role. Before Upajak agreed to serve on the leadership team, she spoke with Khalhek, who alleviated some of her concerns and shared information about the challenges a woman faces as a community leader.

Upajak does have leadership experience. For the past seven years, she served as a public health volunteer for the community. When people returned to the village because of COVID-19 restrictions, Upajak helped manage the process. She was responsible for ensuring that people quarantined properly before resuming everyday activities within the community.

Upajak does not talk about her natural leadership abilities, but they are clear in her personal story.

Her family could not afford to send her away to finish her education. Therefore, she stayed at home and helped manage their land while completing elementary and high school through distance learning.

She values education and is currently supporting her daughter, who is the first in the family to attend college in Nan Province.

Upajak also heads up the Women’s Group in Nam Mhaw, sharing information from the village committee with women in the community. Before Upajak took on this role, women in Nam Mhaw depended on their male family members to receive information and express their views in decision-making processes.

Importance of gender impact assessment

Many of the villagers expressed their bewilderment about our questions on the impacts of forest policies on women and local communities because no one had ever visited the village to talk to the women before. The head of the village, a man, usually spoke to visitors on behalf of the whole community.

From talking with Khalhek, Upajak and other community members, I gained a deeper understanding of how gender inequality is affecting the management of the community and community forest.

Because gender is not taken into consideration, there are no supportive mechanisms to help women gain leadership skills and take on more responsibility in the community. That’s what makes Khalhek and Upajak’s stories unique. They were able to attain a higher level of education than most women in the village, and they had personal drive that motivated them. They also have supportive spouses and families that enabled them to take on more responsibilities. Their inner strength and ambition naturally led them to leadership.

Even though it is not acknowledged by the community members, gender continues to play a dominant factor in the separation of household and paid labour. When alternative livelihood workshops are offered by the government or non-governmental organizations, the village committee recommends who attends largely based on gender. For example, in Nam Mhaw only women were trained to make brooms. And only men were trained to conduct forest patrols in the community forest.

Khalhek and Upajak are breaking new ground in Nam Mhaw, which recently agreed to add another woman to the village committee. They are opening space for new kinds of ideas and questions regarding how the village is managed and responds to changes in forest laws.

With the information from Nam Mhaw and other communities across Thailand, RECOFTC will publish findings of the assessment in 2021 to support policymakers in the development of gender-sensitive forestry policies.

###

Kate Greer is a communication officer with the Voices for Mekong Forests (V4MF) project. V4MF is a five-year project funded by the European Union. V4MF aims to strengthen the voices of non-state actors such as civil society, Indigenous Peoples, private sector and local communities to influence forest governance in Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand and Viet Nam. The project supports FLEGT, REDD+ and other forest governance initiatives.

This story is produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its content is the sole responsibility of RECOFTC, and it does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

RECOFTC’s work is made possible with the support of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida).