“The Forest is Our Supermarket…and We Don’t Need Money”ons of poor rural households, families are

With the steep rise in global food prices pinching millions of poor rural households, families are becoming more dependent on natural resources for their sustenance. RECOFTC –The Center for People and Forests, has been working with local communities living in and around forests in the Asia-Pacific region for 25 years, trying to understand the challenges and solutions for improving their lives through community forestry.

On October 12, 2012, RECOFTC organized its first Executive Study Tour on “Forest and Food Security” for 11 senior government and civil society professionals from four countries in the region. The group visited the ethnic minority Thai Karen village of Ban Huai Hin Dam, some three hours west of Bangkok, and spent the day listening to their story of settlement as refugees 200 years ago, the threat that led to the formation of their community forest in 1995, and what it means for their way of life today.

In a materialistic world, it’s important to remind ourselves that there are also people who regard money as meaningless when life depends on the preservation and skillful use of natural resources. It’s a powerful message that resonated throughout the presentations made in the morning, the lunch served from forest products, and the walk through an organic farm and agro-forest plantation in the afternoon.

Regenerating the forest…and their lives

Tracing the story of the community forest on a hand drawn map, the Village Head Mr. Joe Kueng Ba Ngamying recounts how a logging concession from 1974-89 led to the loss of farming land for the community and destroyed the forests and watersheds, leading to drought, loss of sustenance and great distress for the community. Continued encroachment of the open land even after the concession ended in 1989, brought the community, now 567 strong, together to preserve their environment and their way of life. With support from NGOs, the community forest committee was formed in 1995, boundaries were demarcated, and regulations for the joint and sustainable use of natural resources were put in place.

RECOFTC has been active in the area since 2000, helping the community sustainably manage and monitor utilization of their forest resources through a project called “The Thailand Collaborative Country Support Program” until 2008. Action research on Bamboo monitoring and planning for the community forest was completed by 2004, after which RECOFTC acted as a facilitator for boundary demarcation and resource management. Two years later, RECOFTC included Ban Huai Hin Dam in its youth-focused “Strengthening Young Seedlings Network: Youth Capacity Building for Sustainable Natural Resource Management,” project under which capacity building work still continues.

Today, life has improved visibly for the community: “We get clothes, food, medicine and shelter from the forest,” says Mr. Noei Aimchan, Chairman of Community Forest Committees of Ban Huai Hin Dam. “The forest is our supermarket. When you go to the supermarket, you need money. We don’t need money but we need to educate people how to use the forest.”

Mr. Kwai Ngamying, the local wise man and advisor to the community forest committees, describes a way of life based on inversing the consumerism of the West: “In the West we believe that forests belong to people, but in the East we believe people belong to the forest.” It’s a telling difference fortified by reverence and rituals that have sustained the community for decades. Rituals that include meditating in the forest to know oneself, planting food as offerings for other living creatures and testing one’s wisdom by navigating a maze through the forest during a festive season.

18 years to build trust

To avoid conflict, the community has divided the forestland into zones for growing food, conserving wildlife and plant species, and for human habitation. The creation of a Pu Toei National Park in 1997 presented some problems as it encompassed an area traditionally used by the community for sustainable rotational agriculture. As we walked in that area admiring the abundant vegetables, fruit and grain crops, a committee member explains that trees are felled in a particular way to level a field for planting so that the stumps stay alive and can regenerate when the land is lying fallow. “We had to prove that we could conserve the forest and even improve it with our cultivation methods,” he says, “before the National Park authorities would agree to let us use it. It took 18 years for us to build the trust but we have a good understanding today.”

Through organic farming, the community has ensured a bumper crop of papayas, potatoes, eggplants and bananas and a particular variety of organic rice that is not available in the market. They deliberately introduce different species on residential and forestland to enrich the forest ecosystem and diversify the biosphere. “We don’t use any chemicals here because we make our own organic fertilizer from rice husk and dung,” explains Mr. Kwai Ngamying, as we walk around a compost heap to examine the bark of a medicinal tree. “It’s quite strange, but if you have these leaves when you are sick, you get well. But if you have them when you are well, you may die,” he says, giving us an example of the forest lore which sustains communities even if it seems contradictory to outsiders.

Traditional medicine thrives in the many residential gardens which function as pharmacies, providing a range of remedies for common ailments. Delegates were offered a bitter brew made from forest herbs but many give up after the first few sips from their bamboo cups. I can vouch for the powerful cleansing properties of that drink however, after 24 hours.

Food Security Insurance: A rice bank

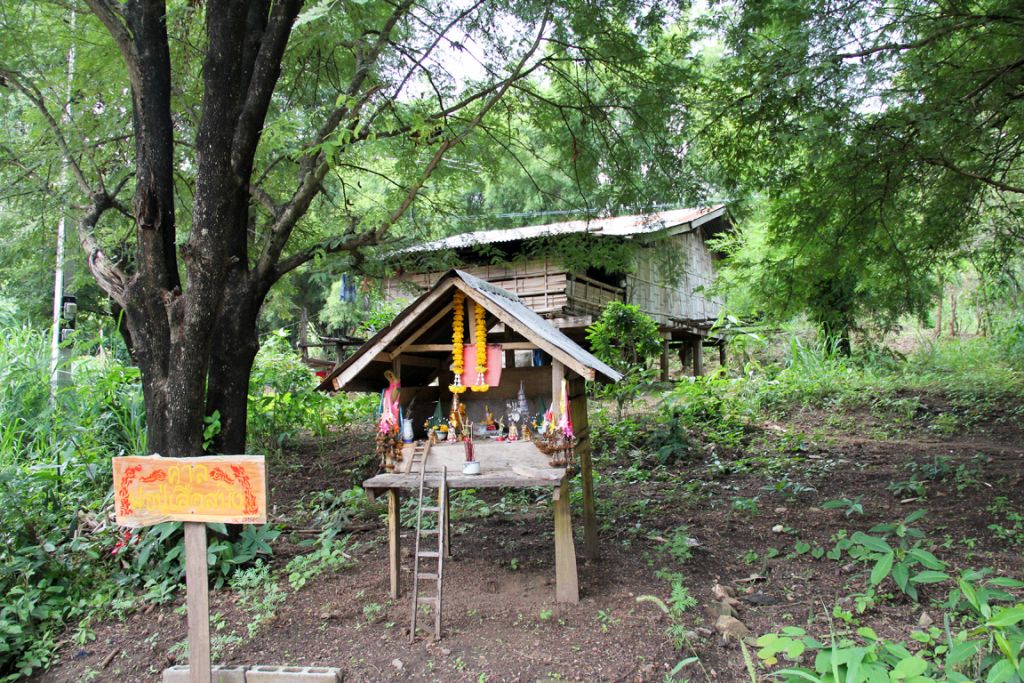

Being the basis of nutrition, a rice bank has been established in a small wooden hut opposite the community hall. Under a barter system, a family may borrow up to 20 buckets (1 bucket = 15 kg.) of rice, but must replace it with 10% interest by the next season. The community also reserves a percentage of their collective cash for the poorest families, ensuring that the food security of all is preserved.

The women of the community make their own important contribution to livelihood activities. Mrs. Lamyai Kongkae, the head of a women’s group from a neighboring village is here today to learn from the study tour discussions. Like the other women in the village, she is attired in a beautiful hand woven sarong and blouse that would not look out of place around the best addresses in town. Young girls are dressed in white by contrast, to signify purity. Pastel pinks, dusky browns, blues and red, the women look splendid in their ethnic creations. A selection of table runners, scarves, bags and other items woven by the women using natural dyes and the finest cotton are on sale.

The delegates buy presents for family members back home and suggest the women take up the activity on a commercial basis. This startles them as they are used to producing and harvesting only enough for their needs. It is what differentiates them from the consumer culture prevalent outside these communities. The villagers don’t see a particular value in acquiring more than they need. As one of them points out: “First you own the land, but later, you become the land.” Trying to instill these creeds in a younger generation is more challenging they say, because development paradigms from the west are impacting their ancient belief systems. As the youth leader says, “In the west you protect forests with fences, here we protect them with love.”