It is always challenging for developers of FLR initiatives to identify the ‘right’ stakeholders and their representatives, and then prioritize them for different levels of engagement in FLR.

The following questions can help. They are based on the work of John Stanturf and colleagues (2017) at the International Union of Forest Research Organizations.

- What are the common livelihood strategies related to the landscape?

- What are the commodity chains related to the landscape and who is involved at each stage?

- How are statutory rights and customary rights claimed by different land-users in the landscape?

- Who pays for or invests time or money in FLR?

- Who is affected by restoration and how?

- Do those affected have the capacity to participate?

- If people need support in order to participate, who provides it?

These questions focus on the rights and entitlements of different groups. This is important in Southeast Asia, where overlapping statutory and customary rights and associated conflicts prevail.

It is also important to look at the commodity chains in the landscape to identify those who are not always visible through the lenses of land use, land ownership or direct benefits. And because the interests, roles and influence of stakeholders can change over time, frequent reviews and updates are needed.

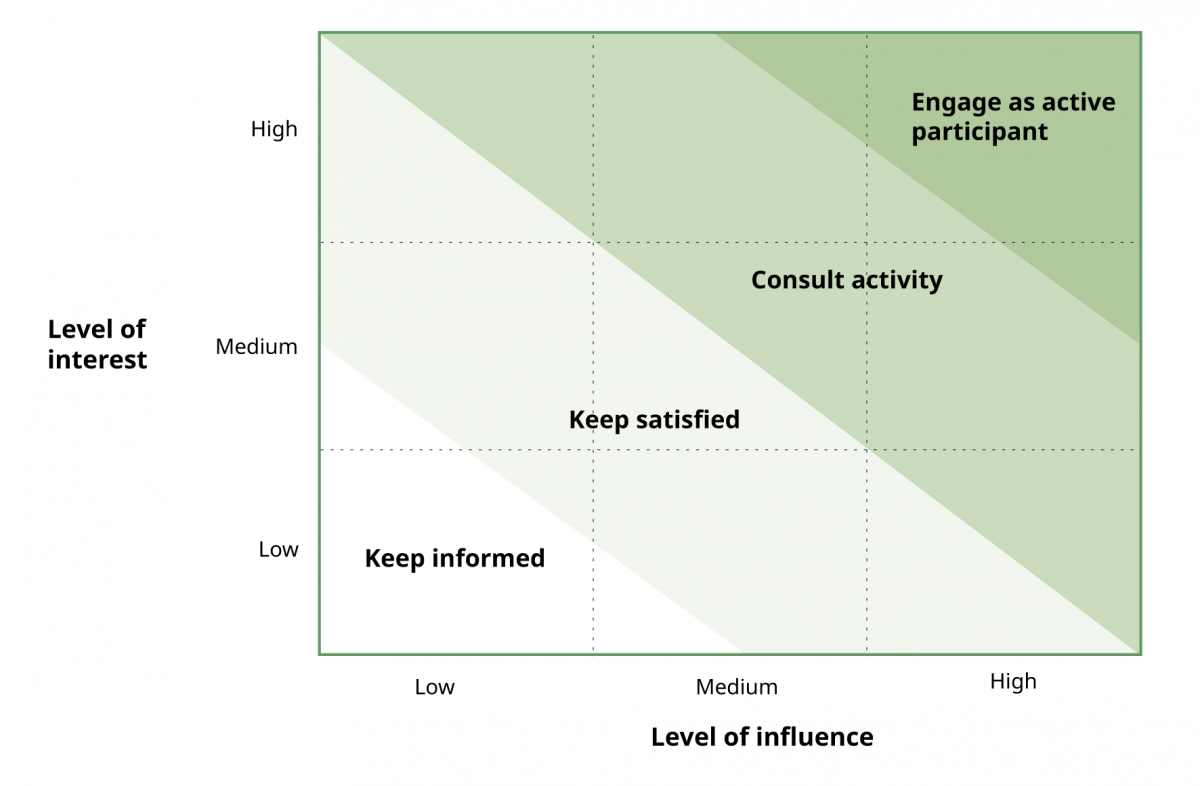

The process of prioritizing stakeholders for engagement is highly contextual. FLR programs and projects may use different sets of criteria, principles or tools to assist this process. In general, levels of interest and influence can be used to prioritize stakeholders and develop strategies for engaging each of them.

Figure 1 shows a matrix that FLR practitioners can use to do this. It groups stakeholders according to their levels of interest and influence. The diagonal bands show which of four simplified engagement strategies might be most appropriate for each stakeholder.

Figure 1. Matrix indicating levels of stakeholder influence and interest

Ensuring that stakeholder groups are balanced and representative is important. It is also challenging, and there is a risk of excluding groups or individuals. A failure to engage local communities and ensure they benefit fairly from FLR can lead to conflicts or lack of compliance. This might undermine or even jeopardize FLR efforts. Government agencies, private sector actors and civil society organizations must therefore recognize, engage and support communities in an effective and equitable manner.

Marginalized people in particular will struggle to enter effective and equitable negotiations. FLR programs should try to close these gaps. Facilitators can use participatory approaches from early on in the process to engage those who are the most vulnerable to changes in the landscape. Capacity building can help ensure these groups are able to take part in discussions and negotiations.

The complexity and importance of multi-stakeholder processes in FLR means that practitioners need to understand the stages where engagement and coordination happen, and potential challenges in each stage.

Public-Private-Civic Partnerships for Sustainable Landscapes: A Practical Guide for Conveners provides detailed instructions on how to engage and coordinate stakeholders from government, the private sector and civil society throughout a sustainable landscape program.