In the mid-afternoon heat, Kong Vuthy sits in a large, open-sided house that serves as a community meeting place in Borie Ousvuay Village in Stung Treng Province. Pictures of the Buddha sitting in a forest adorn the walls.

Kong’s community has witnessed the growth of forests in areas it manages and the destruction of forests in the surrounding land. According to Global Forest Watch data, the village’s district lost 80,500 hectares of forest cover from 2001 to 2018, a 37 percent decrease.

Kong says his community forest has avoided this trend thanks to persistent patrolling. But like many community forest chiefs across the country, he is concerned about the future. Kong believes uncontrolled development could open up the community forest to small-scale land grabbing and illegal logging, especially if local authorities approve a road through the village. With no consistent budget for patrolling, he is afraid that “the community forest will not last”.

Funding gaps are a challenge for many community forests in Cambodia. Recognizing this, RECOFTC worked with the Forestry Administration in Kampong Thom to develop the concept of a community forestry credit scheme in 2014.

A year later, with funding from the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, five communities tested the model. By 2019, there were 29 schemes in four provinces.

New approaches to old challenges

Each credit scheme provides low-interest loans that community members can use to invest in their landscape. The interest that borrowers pay increases the overall fund and covers the costs of administration and implementing community forestry management plans.

In Prey Kbal Bey Community Forest, for example, the credit scheme charges 3 percent interest. Although this is more than some microfinance systems charge in Cambodia, the lack of a need for collateral and the communal management make the scheme attractive to borrowers.

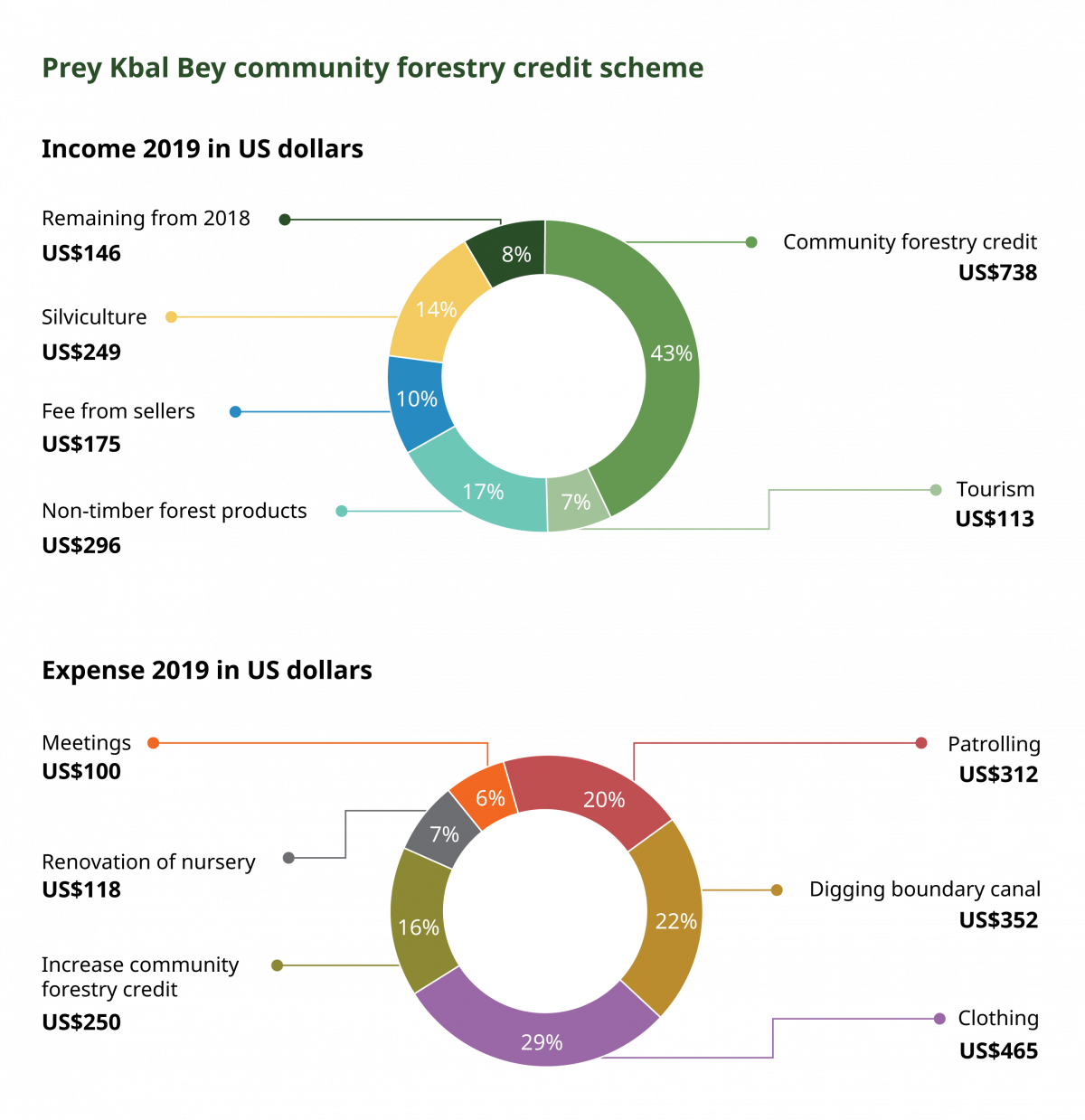

The credit scheme replaces informal loans that charge much higher interest, demand collateral and are off the books. In 2019, the credit scheme provided 43 percent of the Prey Kbal Bey Community Forest management group’s annual income.

Members of the nearby Thbong Domrey Community Forest have used loans from their credit scheme to invest in small agriculture businesses, thus diversifying income streams. Villagers can borrow up to US$250 and pay it back within three to six months. Since it started in 2015, the credit scheme has grown to approximately US$9,375.

Credit schemes can also redress local elite capture and gender disparities. More than half of the 931 members of the 29 community forest credit schemes are women.

Lok Lai Seurng, Deputy Chief of the Thbong Domrey credit scheme, says that increasing women’s participation in the management committee has opened up space for women to decide how the community forest is managed.

“When women participate in the community forestry credit scheme, they are able to engage more in the management process,” she says. “This is because they are better informed about what is happening and can decide how the credit scheme funds are used to best manage the forest.”

Challenges ahead

Credit schemes and alternative livelihoods are important technical solutions. But political challenges such as poor governance, gender disparities and weak legislative frameworks must be mitigated, too. And as Cambodia enters its second wave of decentralization and begins to transfer authority over large areas of land from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries to the Ministry of Environment, the technical and political challenges will only become more apparent.

For example, despite RECOFTC’s efforts in 2017 to create technical guidelines on the transferring of community forests to community-protected areas, there is still no endorsed framework for doing so. This threatens to leave communities between legal frameworks and, in some cases, more vulnerable to illegal logging and land grabs.

Under the new decentralization policies that came into effect on 1 January 2020, the power to establish community-led forest programs has moved from provincial forestry officials to provincial governors and other local authorities.

The impact of giving local authorities the power to make final decisions about forests has yet to be seen. Some of these local authorities have limited experience with community-led forestry practices but with their history of opposition it is certain that they will be pivotal figures.

This suggests that organizations and the Government must also work on finalizing legal instruments that fit the current situation and improve tenure security. There also must be a more concentrated effort on vertical capacity-building. Organizations need to work with decision-makers at the national level, where laws are made, and at the provincial and local levels, where laws are implemented.

A legacy to build on

At the core of community forestry and community-protected areas are the many people who have worked to create a better future for their communities and their country. Their story is one of persistence and hope despite the overwhelming odds and unfavourable systems.

“The main legacy is the people,” says Cor Veer, who taught courses on community forestry for RECOFTC in the 1990s.

The communities, practitioners and government officials who established community-led forest management continue to work to tackle the fundamental problems that are slowing down success. This is generating hope as Cambodia’s communities and forests enter the next period of their shared history.