By the early 1990s, the first seeds of modern community-led forest management were sown. It began around 1992, when the Mennonite Central Committee relief agency piloted a project in Cambodia’s Takeo Province. Soon after, Concern Worldwide, the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations each began similar projects elsewhere. But the scope of their projects was limited. Community forestry would retain a low profile throughout the 1990s.

At the same time, a small cadre of Cambodian government officials whom RECOFTC had trained in neighbouring Thailand were starting to see community forestry as a potential alternative to forest concessions. Vong Sopanha, now Deputy Director-General of the Forestry Administration, was a member of this early generation of community forestry practitioners in Cambodia.

“Community forestry was new to me,” she says of her four-month course at RECOFTC in 1993. “But I brought the idea and my experience and tried to apply it to Cambodia.”

The political and economic situations favoured continuing with forest concessions, as did the major donor policies at the time. Forest concessions remained the main tenure system for natural resource management in the 1990s. The little land communities received was degraded. More valuable land was allocated to investors through concessions.

A lack of trust also held community forestry back. Government officials, particularly at the local level, doubted that communities could sustainably manage the land. Years of impunity for forest crimes had shattered societal trust in the State.

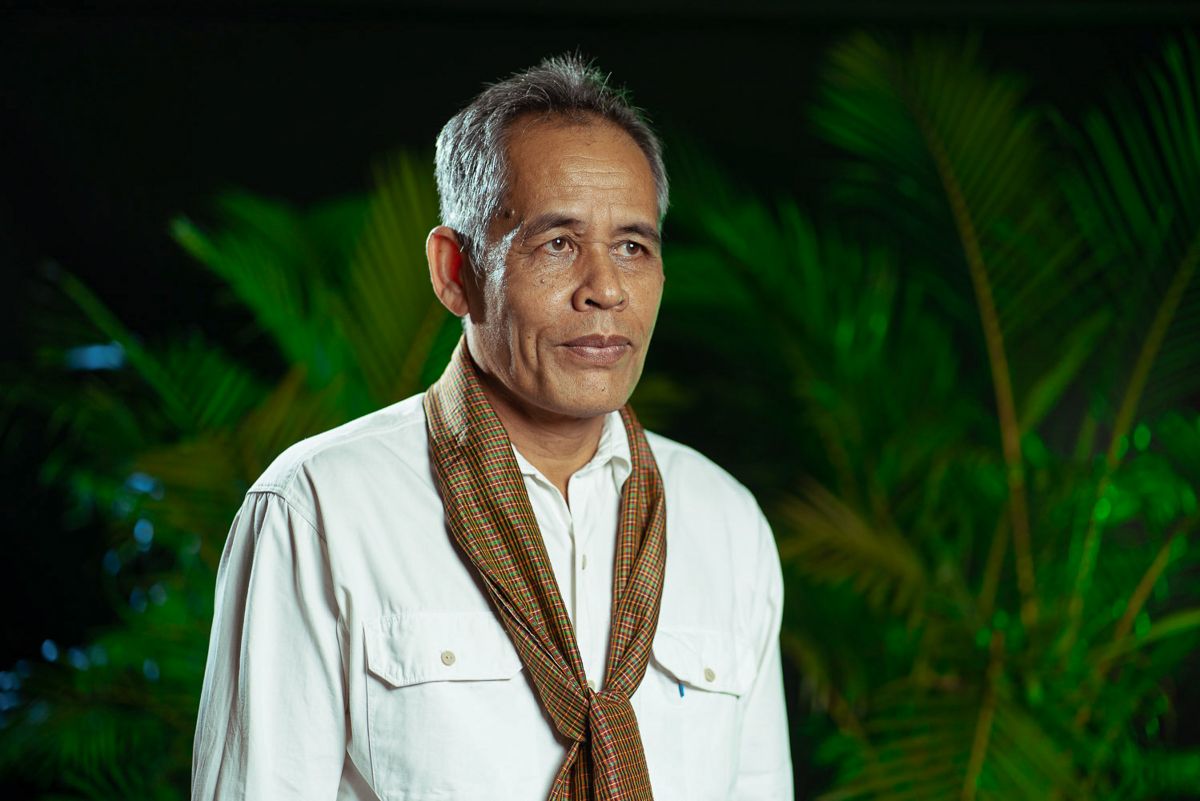

Kim Sarin, Deputy Director of Local Communities in the Ministry of Environment, says some people feared that community forestry was an attempt by the Government to take their land. To others, it sounded too similar to the collective ownership the Khmer Rouge regime had imposed 20 years earlier.

Despite these odds, Vong and other early community forestry practitioners in Cambodia made significant strides. In 1996, IDRC and RECOFTC supported the first training in Cambodia on community-led forestry. Ten staff each from the Forestry Administration and the Ministry of Environment attended the two-week course and did field studies in Pursat and Kampong Chhnang provinces.

The officials who attended the courses in Thailand and Cambodia began to train colleagues in the government and developed informal networks to promote community-led forestry within the ministries. The message was spreading.

Other shoots

In the same year that RECOFTC offered the first course in Cambodia, the Department of Forestry and Wildlife and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries drafted a sub-decree on community forestry and submitted it to the Council of Ministers. The Council of Ministers put the sub-decree aside until 1998, when it formed a Community Forestry Working Group to revise the draft. Meanwhile, Concern Worldwide, IDRC and GTZ established the Cambodia Community Forestry Training Team to build up the skills of practitioners and government staff. RECOFTC had already trained many of the team’s members.

Community-led forestry models did not progress inside a political vacuum. In July 1997, the coalition Government broke down. In the 1998 election, the coalition formed again, with CPP as the dominant partner and centralizing all military power.

During those two years, a series of defections weakened the Khmer Rouge. Pol Pot and the three other leaders were soon overthrown. Pol Pot was placed under house arrest, where he would die in 1998. The Khmer Rouge then disintegrated. After 30 years, Cambodia was at peace.

The end of the conflict allowed the Ministry of Environment to observe the situation in the country’s protected areas. Five years earlier, the Ministry had established 23 of these areas. But the war with the Khmer Rouge in the west and the poor road conditions in the east had made many areas inaccessible.

In 1998, Ministry officials were finally able to enter some of them for the first time. “When they did, they were surprised to find communities living in and near the protected areas and using the forests for food, timber, medicines and income,” says Kim, Deputy Director of Local Communities in the Ministry of Environment. “The Ministry did not want to remove the communities.”

The following year, the Ministry piloted four informal “community-protected areas” using a model similar to community forestry. The Ministry’s aim was to engage local communities in managing the forest. A parallel model was born.

While community forestry was taking its first steps in Cambodia, the Government was trying to entice back international donors that had withheld aid after the violence of 1997. As part of its efforts, it introduced measures in 1998 and 1999 to crack down on illegal logging. Ironically, by targeting smallholders rather than concessionaires, they centralized control over logging rights.

In “The Political Ecology of Transition in Cambodia 1989–1999” Philippe Le Billion says this gave exclusive rights to a few concessionaires to exploit forests.

More problems with the concession system became clear in a series of reviews that international donors commissioned. In 2000, for example, the Asian Development Bank’s report Cambodia Forest Concession Review described the commercial timber industry as “a total system failure, resulting from greed, corruption, incompetence and illegal acts that were so widespread and pervasive as to defy the assignment of primary blame”. Pressure was again mounting on Cambodia’s concession system. Reform was on its way.