Thailand’s Citizens’ Forest Network, which formed in 2018, brings together 34 civil society organizations and hundreds of community forestry groups across the country. It focuses on ensuring that people who depend on local forests can play active roles in sustainably managing and benefiting from those resources. This involves developing partnerships between communities and local governments, influencing policy and legal reforms, building capacity, doing research and raising awareness.

Interviewees were asked which factors would influence the network’s effectiveness. One person stressed the need for a complementary mix of experiences and competences, adding that this increases trust in the network among both its members and the government: “The Citizens’ Forest Network benefits from the diversity and complementarity of expertise of leading organizations within the secretariat, with one more focused on conservation, another focused on livelihoods and citizens’ rights, and another being good on integrating green and people-centred approaches.”

“Ownership must be with all participants.” – Member of civil society network from Thailand

Independence and cohesion are also important, said another member: “It is important to not get trapped by donors and to not get owned by individual network member organizations. Ownership must be with all participants.”

These are just some of the factors that network leaders and members mentioned in interviews with the study team. In fact, interviewees in most countries identified a similar set of factors.

The three factors promoting effectiveness that interviewees in 11 of the 12 countries mentioned were financial autonomy and resource mobilization; communication and information-sharing; and commitment and motivation.

“The network must have a certain level of information exchange that comes either from the network coordination unit, its members or its partners,” said one interviewee from Cameroon. Another said: “Dynamism here means the network communicates about its actions and the actions of its members and also the network ensures its visibility, and that of its members.”

On the issue of finance, an interviewee from Ghana said: “Continuous funding ensures effectiveness.” One from Liberia said that: “Internal income generating mechanisms can help reduce dependency on external donor funding and ensure financial viability of the organization.”

It is notable that while the networks themselves emphasized finance in this way, representatives of governments did not seem to indicate the lack of funding as a challenge for networks.

"Internal income generating mechanisms can help reduce dependency on external donor funding and ensure financial viability of the organization." – Member of civil society network from Liberia

In 10 countries, interviewees mentioned internal governance and structures, and expertise, capacity and skills. For example, one from the Democratic Republic of the Congo emphasized, “having the technical capacity to carry out these activities and achieve these objectives successfully.”

And in nine countries, interviewees mentioned unity and speaking with a common voice, and the network’s ability to function as a learning platform for capacity building. “The element that catalyses the effectiveness of the network is cohesion,” said one from the Republic of the Congo. Another from Liberia said: “Togetherness and sharing information with each other make us more effective in what we want to deliver on.”

Network leaders and members highlighted the importance of sharing certain values such as adaptability, trust and harmony, accountability, autonomy, transparency, work ethics, patience, innovation and creativity. Interviewees at international NGOs also mentioned values such as transparency, neutrality, unity and innovation. They were, however, most likely to mention knowledge, expertise, advocacy skills and sustainable funding as internal factors promoting the effectiveness of networks.

Donors were the only interviewees to mention the importance of digital access, use of social media and digital security. This is important for networks to consider in the context of effective working practices and the safety of individuals who may be working on sensitive issues.

“The international NGOs also highly rated synergies, complementarities and sustainability of supported initiatives, as well as commitment, engagement, availability and accountability of members,” says Aus der Beek. “They said it is important for network members to work together, based on consensus and cohesion, and so avoid competing according to their individual interests. This depends on strong leadership and network management, as well as related internal governance and structure.”

Network leaders and members also highlighted some internal challenges that can limit effectiveness. These included a lack of clarity about roles and responsibilities, conflict or competition among members, and turnover of network members.

“It is hard to find people with good knowledge as they leave for other organizations,” said an interviewee from Lao PDR. “We try to attract highly educated people to work with us, but it’s difficult as we don’t have so much income to offer.”

Comparing regions

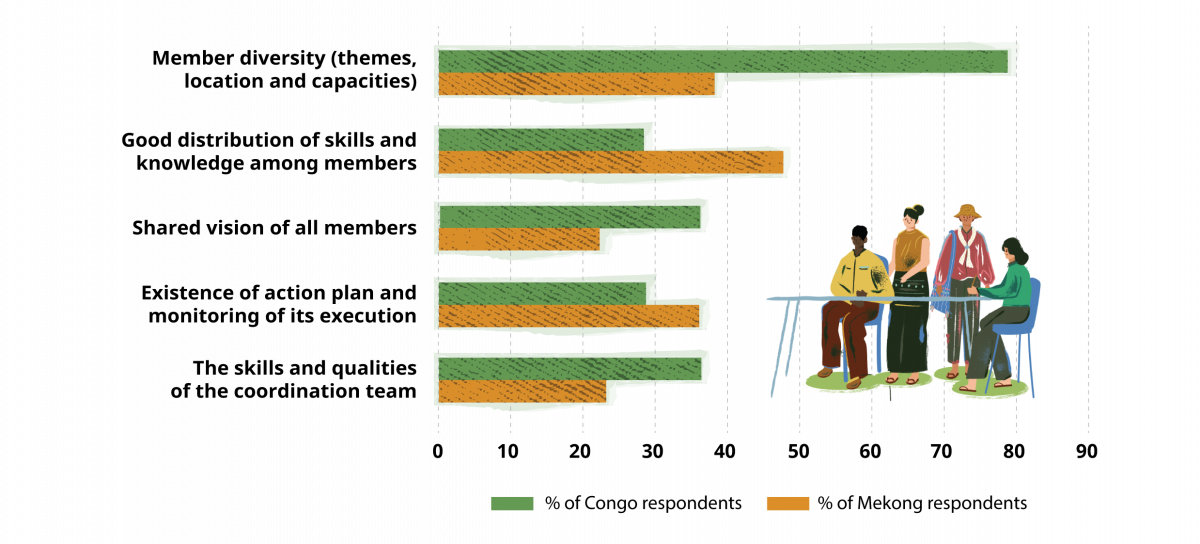

The online survey allowed the study team to explore regional differences in the internal and external factors that help or hinder networks. In the Congo Basin, 79 percent of respondents overwhelmingly identified the diversity of a network’s members as being a key factor promoting effectiveness (Figure 4).

In the Mekong region, 48 percent of respondents identified the distribution of skills and knowledge among network members as an important factor. All of the other factors, such as shared vision between the members, the decision-making process or the structure of the network, were fairly evenly selected by network members in both regions.

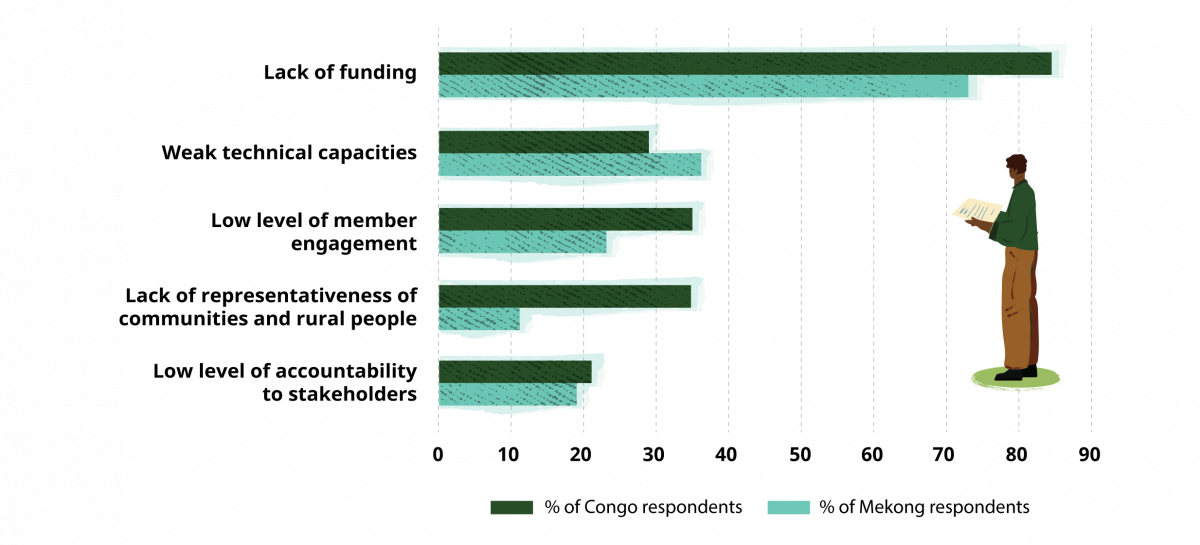

In both regions, large majorities of respondents identified a lack of funding as an internal barrier (Figure 5). About a third or less of respondents in each region identified any of the other options as being important internal barriers, including the low level of members’ engagement or the lack of representation of communities.

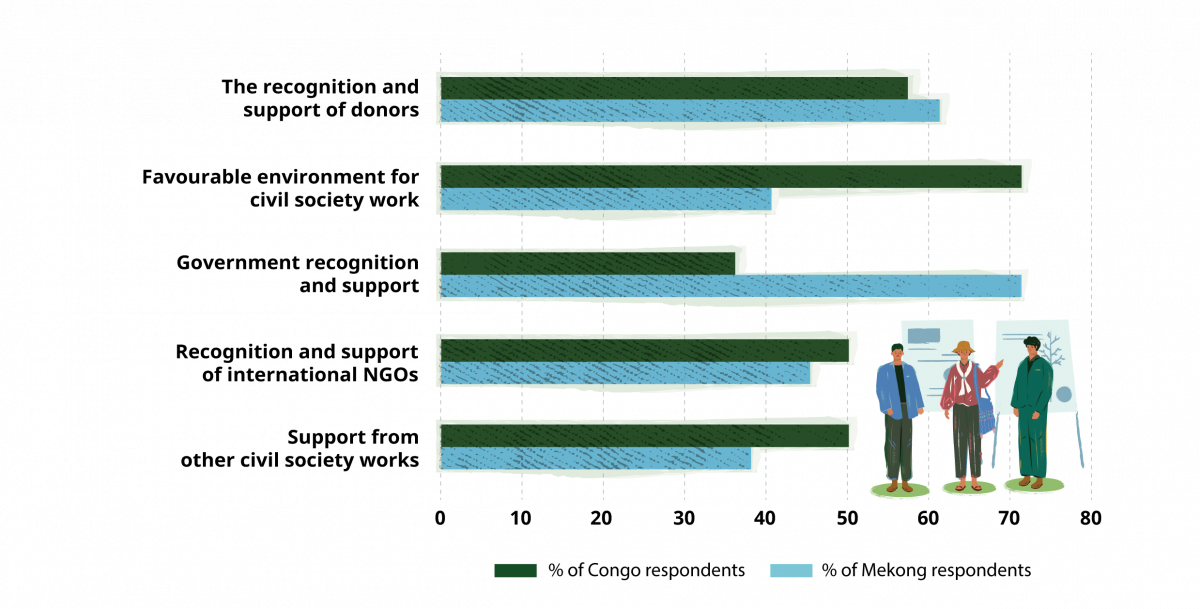

Among external factors promoting network effectiveness, large majorities of respondents in the Mekong region identified recognition and support by government (71 percent) and by donors (61 percent) as important (Figure 6). In the Congo Basin, majorities of respondents identified a favourable working environment for civil society (71 percent) and recognition and support of donors (57 percent).

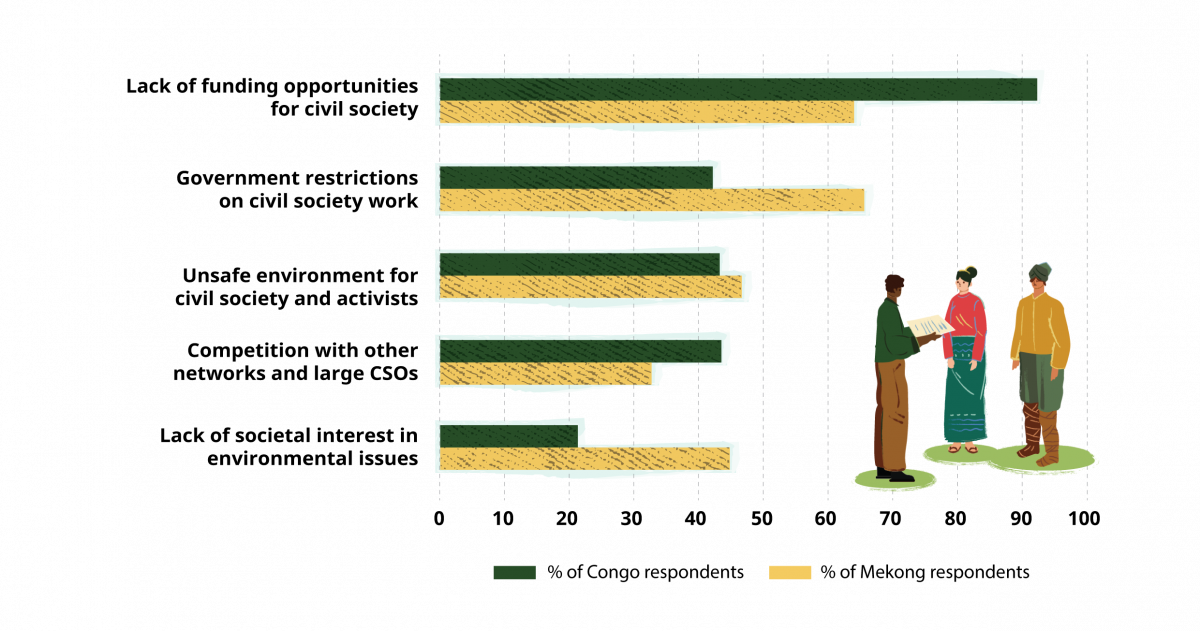

In both regions, a majority of respondents said a lack of funding opportunities limited effectiveness: 91 percent from the Congo Basin and 65 percent from the Mekong (Figure 7). In the Mekong, a majority also identified government restrictions on civil society work as a factor to take into account.

It is notable that large majorities of respondents from the Mekong region highlighted the importance of government recognition and emphasized government restrictions as a challenge to their work. In this region, CSOs have to comply with several requirements, including those relating to their procedures, eligibility and reporting. Processes in which governments seek contributions from civil society, such as FLEGT Voluntary Partnership Agreements and REDD+, can create opportunities for networks to gain the recognition they need to perform their work. But perhaps more than in the Congo Basin, this may demand networks in the Mekong region to tread a fine line between engaging in advocacy and collaborating with national governments to contribute to those processes.

Concerningly high proportions (more than 40 percent) of respondents in both regions identified an unsafe environment for civil society and activists.

“Many of the processes in which civil society organizations intervene promote good forest governance with a peaceful and open participation of all stakeholders, including civil society,” says Faure. “But the lack of security experienced by civil society networks, whether it is through a restrictive legal or political environment or other types of threats such as physical ones, may seriously challenge the quality of that participation. This must be taken into account when assessing the results of a specific process. In addition, monitoring how safe the environment is for civil society to operate and creating safeguards for their meaningful participation are key areas that these processes can themselves help to improve.”