Since 2010, tropical countries have made varying degrees of progress reducing greenhouse gas emissions from their forest sectors under the UN’s REDD+ scheme. REDD+ could help finance forest protection and sustainable forest-based livelihoods. However, there are also concerns that vulnerable communities could lose their rights to use local forest resources, which they have used for generations.

Aware of such risks, CSOs in Cambodia joined forces in 2012 to form the CSO REDD+ Network. Its goal is to ensure that the government consulted civil society and incorporated its views in national REDD+ policy development and implementation. Through its activities, the network has promoted transparency, accountability, participation and other aspects of good forest governance. It has contributed to the development of Cambodia’s REDD+ Action and Investment Plan, the country’s prakas or guidelines for the REDD+ greenhouse gas mechanisms, and safeguards to mitigate potential negative impacts arising from REDD+.

“Acting individually, the 32 members of the CSO REDD+ Network would unlikely have achieved what the network has,” says Aus der Beek. “But while it is clear that there is power in a union, being effective is more than just a matter of having strength in numbers. Understanding effectiveness is crucial not only for civil society networks, but also for the governments, donors and international organizations that interact with them.”

Understanding why networks like the CSO REDD+ Network form, what they do and how their members benefit are important to understanding their effectiveness. In some instances, the reason and conditions behind the creation of networks may directly impact their effectiveness.

“The environment in which a network is formed can offer good insights into its functioning and the challenges it faces,” says Nathalie Faure, senior program officer for governance, institutions and conflict transformation at RECOFTC. “I have witnessed the lasting struggles of a network in the Congo basin that was formed to fulfill the requirement of a political process, without having a strong internal drive from civil society organizations to come together. However, the networks’ own evolutions show they are adaptable, and other networks created in better conditions continue to thrive.”

“While it is clear that there is power in a union, being effective is more than just a matter of having strength in numbers.” – Robin aus der Beek

The study showed that the need and opportunity to engage in political processes, such as VPA negotiations and REDD+, influenced network creation in the other countries the study surveyed. The only exception was Gabon, whose network formed largely to meet the needs of communities that depend on forests.

“Engaging with political processes can bring benefits, including access to capacity building and resources,” says Zora Nina Tbatupe, technical assistant at FLAG. “It can also give civil society organizations a seat at the table to engage in important national dialogues. But networks can also be exposed to certain risks if the process comes to an end or if funding is no longer available to support their meaningful participation or role.”

In the Central African Republic, all of the respondents to the online survey said the political process was the only reason for their network’s creation. Elsewhere, some respondents identified other reasons alongside political processes. Some highlighted the influence of donors and international organizations. Others said their networks had formed organically to meet their founder members' needs or to fill gaps left by other networks. This suggests that when networks form it is often because of a variety of interconnected drivers. The perceived importance of these drivers can vary greatly within networks.

This diversity of perspectives is also apparent in the variety of responses people gave when asked to identify the main objectives of their networks. In both the Mekong region and the Congo Basin, at least one fifth of respondents selected each of the options listed in the questionnaire. In both regions, respondents most often selected the same five suggested network objectives: advocacy, information sharing, training and capacity building, information exchange and mobilization, although in a different order in each region. They were less likely to select innovation, evaluation, research or combination.

In the Mekong region, 80 percent of respondents selected “sharing information with the wider public” among the objectives of their networks; 58 percent selected “information exchange”; and 54 percent selected “training and capacity building”. All other answers were selected by less than half of the respondents.

In the Congo basin, 86 percent of respondents selected “advocacy”; 64 percent selected “training and capacity building”; 57 percent selected “information exchange”; and 50 percent selected “mobilization”. All other answers were selected by less than half of the respondents.

The survey suffered from some ambiguity in the difference between the meanings of “information sharing” with the public and “information exchange”. Looking at these options together, shows that about 90 percent of respondents from the Mekong region, and almost 80 percent from the Congo Basin, selected one or both of these options.

“Our analysis shows that facilitating information sharing with the public, targets of advocacy or among network members is a very important role that networks of civil society organizations play,” says Faure. “Networks are often seen as spaces of information sharing and learning among members and with external stakeholders.”

Another finding relating to the purpose of the networks concerns whose needs networks serve. When presented with a range of choices, survey respondents in both regions were most likely to say that responding to the needs of vulnerable groups, including communities, women, youth and Indigenous Peoples was most important.

How network members benefit

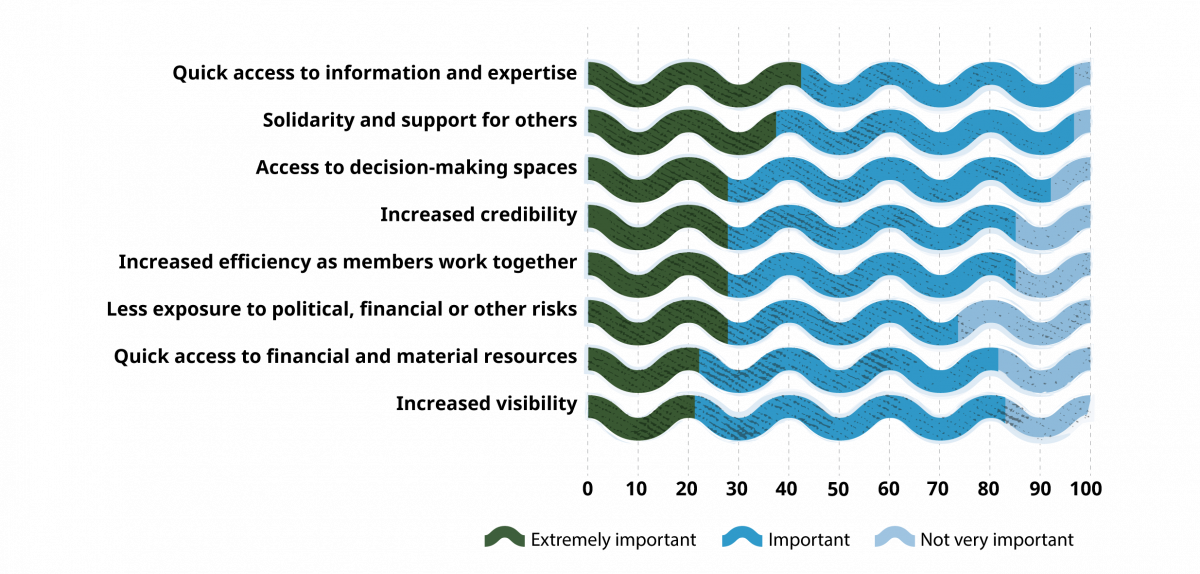

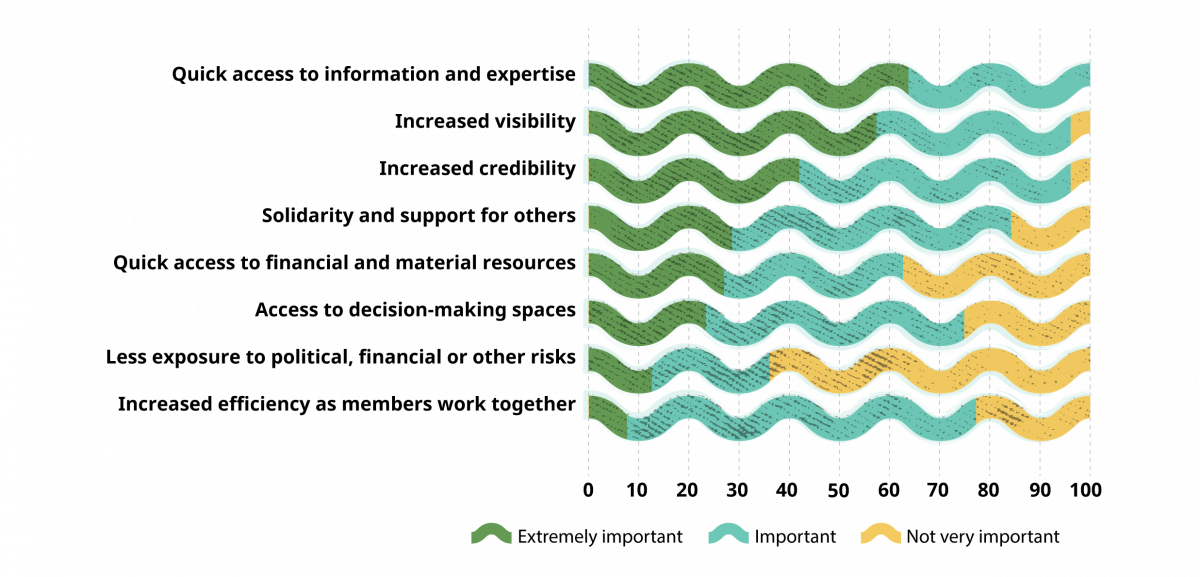

The survey asked respondents to rate the importance of eight benefits obtained from their engagement in their network. In the Mekong region, for all eight options, at least 70 percent of respondents said they were important or very important (Figure 1). In the Congo Basin, this was true for six of the eight options (Figure 2).

In both regions, “Quick access to information and expertise” was the benefit that most respondents valued most highly. This was followed in the Congo Basin by “increased visibility” and “increased credibility”, and in the Mekong region by “solidarity and support for others”.

On the other hand, mitigation of exposure to risks, such as political and financial ones, is not considered a very important benefit of their network’s engagement by 67 percent of respondents from the Congo Basin. A fairly large proportion (38 percent) of these respondents also said “access to financial and material resources” is not a very important benefit they gain. These two kinds of benefits were also the lowest rated by respondents in the Mekong region, although a majority of respondents there still said each was important.

“Our findings suggest that the priorities and expectations of network members can sometimes differ from those of the networks themselves, as when a network is focused on advocacy but its members seek capacity building, access to funding, and so on,” says Aus der Beek. “Where there are mismatches in objectives, this might negatively influence member engagement in collective actions if members do not see how their individual organizations will benefit from those actions.”