The Samaky Trapaeng Totim Community Forest in Preah Vihear Province is a source of food, materials and medicinal plants for 322 member families, who are mostly Kouy Indigenous Peoples. Since formalizing their rights to manage the area with PaFF’s support in 2016, the villagers say the forest quality has improved and the density and diversity of forest products they can harvest has increased.

“If we hadn’t formalized the community forest, I am sure that it would have vanished like the surrounding area that is now private farmland,” says Ton Mean, chief of Samaky Trapaeng Totim Community Forest. Thanks to PaFF’s activities, thousands of rural Cambodians like Ton Mean can now exercise their rights to manage, protect and benefit from local forest and fishery resources. To do this, PaFF focused on strengthening capacities among communities and government agencies, from the local to the national level. The resulting growth in the formalization of community-based natural resource management is sustaining livelihoods, reducing poverty and increasing people’s resilience to economic and environmental shocks.

Expanding community-based natural resource management

Around 65 percent of rural Cambodians depend on local natural resources for their livelihood and food security. But many people lack secure rights to take advantage of these resources. To address this, the Cambodian government developed three approaches that allow communities to formally apply for rights to manage local resources: community forests, community fisheries and community-protected areas.

Relatively few communities have seized the opportunities that the government’s three models provide. This is in part because they lack the knowledge, skills and financial resources to request formal recognition and to implement plans for managing resources sustainably. The urgent need to scale up adoption of these models prompted PaFF to work with communities to raise awareness of their rights, register their community forests, fisheries and protected areas and to develop and implement the required management plans.

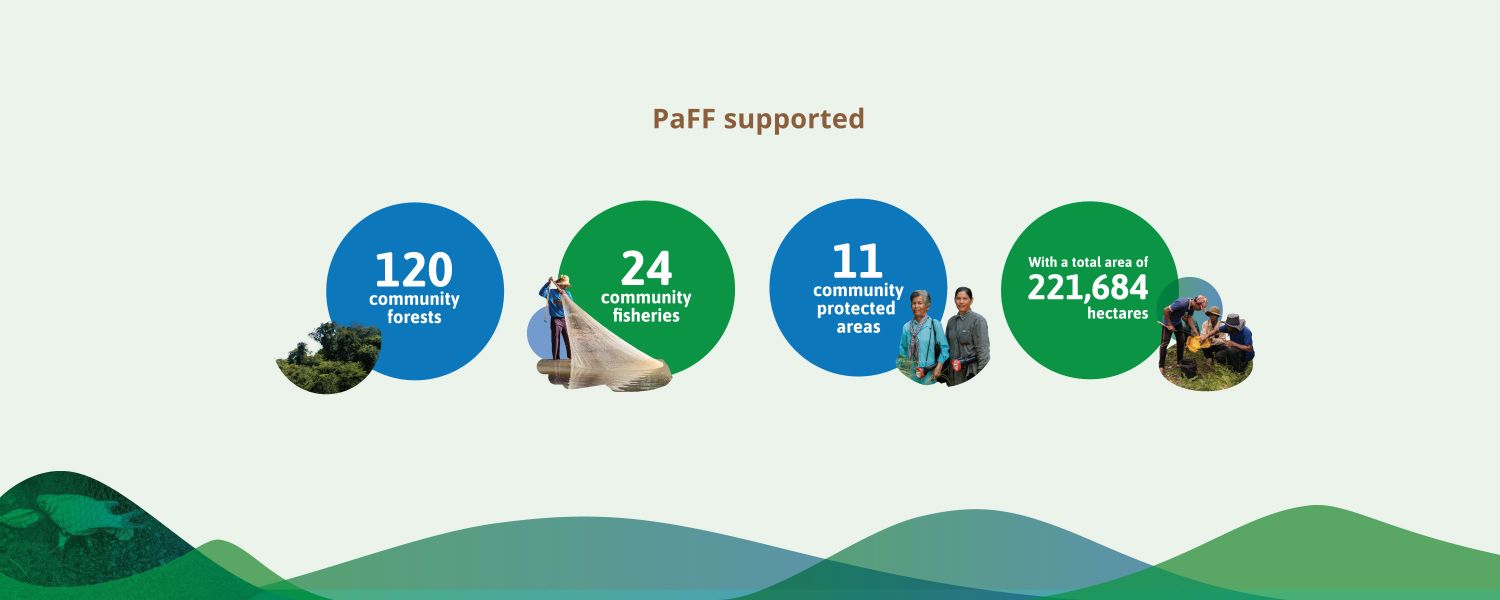

In total, PaFF supported 120 community forests, 64 community fisheries and 11 community-protected areas. Together, they cover more than 221,000 hectares, or nearly 5 percent, of the total area of the four provinces in which PaFF was implemented.

PaFF also supported the preparation of management plans for 172 sites. National authorities had approved 122 of these plans at the time of writing, with the remainder awaiting approval. Official approval of these plans ensures the rights of the local communities over natural resources and provides the basis for securing and improving livelihoods.

“Rural Cambodians depend heavily on natural resources for their livelihoods but are not always aware of their rights to manage these resources,” says Markus Buerli, SDC Director of Cooperation in Cambodia. “PaFF has closed this gap, enabling tens of thousands of people to secure access to local resources and the rights to manage them collectively. This has improved livelihoods and boosted people’s resilience while contributing to Cambodia’s efforts to address climate change and protect nature.”

Improving livelihoods

Community forests, fisheries and protected areas alone cannot sustain local people, most of whom have other livelihoods. But these areas do provide important resources for subsistence and commercial uses—from wild honey, mushrooms and bamboo shoots to rattan and wood for building. In 2019, for example, 50 member families of the Prey Kbal Bey Community Forest in Kampong Thom Province harvested around 3,000 kilograms of a wild fruit (Willughbeia edulis, or kuy in Khmer) with a market value of USD 15,000.

To help communities make more of such resources, PaFF established and supported 35 community-based enterprises selling honey, palm-leaf products, ecotourism services and other goods. The partnership assisted these businesses by identifying investment opportunities, improving business planning and linking producers to buyers. These and other income-generating activities, such as agroforestry, which PaFF piloted in ten community forests, improved the livelihood of around 1,000 participating households. In 2018, for example, PaFF helped members of the Prasat Teuk Khmao Community Forest in Kampong Cham Province set up a honey-collecting group, develop regulations and register with the commune council. The partnership provided training in sustainable honey harvesting, bookkeeping, entrepreneurship and business plan development.

PaFF also connected the new enterprise with buyers and provided USD 1,200 in start-up capital. The following year, the 35-member enterprise generated more than USD 30,000 of income, with a net profit of USD 8,452.

However, PaFF found that although community-based enterprises for some forest products show promise, their potential for growth remains challenged by weak internal capacities, limited linkages with market actors and challenging regulatory environment.

Local livelihoods also benefited from PaFF’s introduction of credit schemes to community forests, fisheries and protected areas (see chapter 4). Borrowers used their loans to start small businesses, pay for their children’s education, buy fertilizers and other agricultural inputs and invest in activities such as growing cassava and raising chickens.

“I can borrow money from the community forest credit [scheme] when I need to buy fishing nets,” says Kea Ra, a member of the Prey Kbal Bey Community Forest. “It is easier and takes less time than borrowing money from microfinance institutions.”

Credit schemes, which remain ongoing, prioritize the needs of marginalized members of communities. Samrith Bunthom, a woman living with disability and member of the Phum Thmei Community Fishery in Stung Treng Province, received a USD 250 loan that saved her chicken-raising and home-gardening business from failure during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“My chickens would be dead if I had no community fishery credit scheme to support my business,” she says. “The credit not only saved my business but also helped solve my family’s [financial] problem during the pandemic. Now my chickens are growing well, and I can sell them to generate more income, while my home garden is also growing well for daily consumption and for selling in my village.”

Formalizing community forests, fisheries and protected areas empowers people to use and protect these resources. This is crucial because many communities face threats from illegal loggers and fishers, land encroachers and unsustainable development. Chapter 2 describes how PaFF supported communities to reduce these threats.