On 17 April 1975, the Khmer Rouge communist guerrillas took control of the capital Phnom Penh after eight years of civil war, and forced two million people living there into the countryside to implement an “agrarian revolution”. The regime’s genocidal policies would claim at least 1.5 million lives. But by 7 January 1979, an alliance of defectors and the Vietnamese army pushed the Khmer Rouge back to areas near the western border with Thailand. They renamed the country the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK).

Forests were low on the PRK’s list of priorities. It had a broken economy to fix, a devastated population to heal, and lingering civil war to fight with the retreating Khmer Rouge. In the early 1980s, its forest sector policies focused on taxing forestry products and requiring permits to transfer logs between provinces. But the ongoing civil war made it difficult to implement and monitor the new regulations.

Both sides of the conflict benefited. The PRK only controlled some of the forests. The armed faction of the Khmer Rouge controlled areas near the border with Thailand and soon began to strike logging deals with Thai military groups in exchange for supplies and refugee protection.

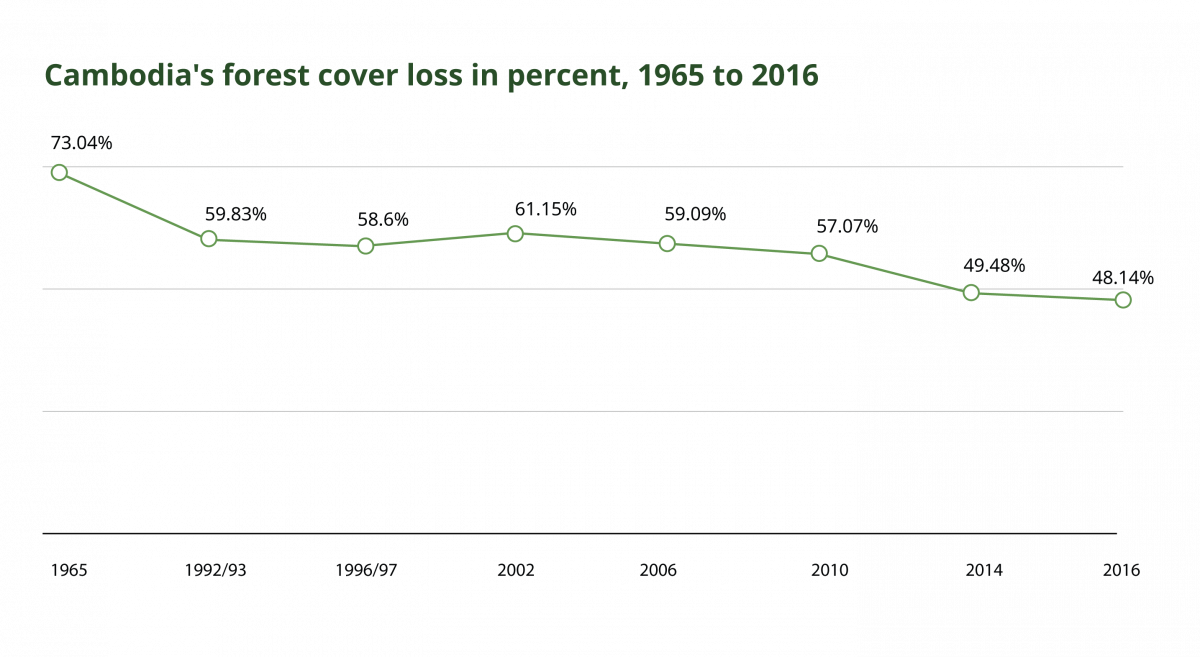

A 1965 study by the Forest Research and Education Institute concluded that forests covered 73 percent of Cambodia. The decade and a half of political upheaval that followed shielded much of the country’s forests from regional logging interests.

While other Southeast Asian forests were plundered, Cambodia’s forests remained relatively intact. This meant rural communities away from the conflict in the western side of the country could still access abundant resources, despite government regulations on harvesting and transportation.

Communities in Kampong Thom Province and neighbouring Stung Treng Province recall this period as one of limited land conflict. With state ownership yet to be codified, they could exercise their customary rights over land and forests, using them for daily household consumption.

“We had full ‘rights’ over timber harvesting and could cut what we wanted,” says Koun Moun, chief of Prey Kbal Bey Community Forest in Kampong Thom Province. “There was no tenure or ownership. Plus, there was plenty of available land.”

But change was coming. In 1985, the new prime minister Hun Sen declared that forestry would become one of the Government’s four “spearheads” to liberalize the economy. Within four years, the country moved closer to a market economy and was renamed the State of Cambodia.

The new timber frontier

Andrew Cock notes in Governing Cambodia’s Forests, the Government’s new focus on timber came as supplies to international markets from other Asian countries were declining. Logging profits in Cambodia had been minor compared with the aid delivered by large geopolitical actors such as China, the then-Soviet Union, the United States and Viet Nam. But aid levels plummeted as the Cold War drew to a close.

To replace aid, Cambodia began issuing major logging concessions to businesses linked to the Thai military. But the ongoing civil war in Cambodia that had grown to involve four armed factions made it difficult for its government to control logging. And when Thailand banned logging in 1989, its logging corporations and military sought to increase their timber supply from Cambodia. They often worked with civilian and military authorities in territories held by the Khmer Rouge. As the global community scrambled to generate a peace deal, conflict increased, with both sides funded by timber revenues.

When all four armed factions signed the 1991 Paris Peace Agreement, it spurred hope that the rampant logging that had fuelled the conflict would end. But the Khmer Rouge reneged on the deal. Its position in timber-rich areas of northwestern Cambodia, notably Palin Province, helped perpetuate the conflict. By now, regional logging companies were hungry for Cambodian timber, and they were willing to work with both sides to get it.

Capitalist anarchy

In 1993, the Cambodian People's Party and the royalist party, FUNCINPEC, formed a coalition. Logging would become a major source of income.

The World Bank and other development agencies pushed logging concessions to promote sustainable forest management and generate revenues with which to rebuild the country. In reality, the concessions and forest rents continued the armed conflict and maintained the webs of political patronage emerging in both coalition parties.

As competition between the parties intensified, so too did the unsustainable issuance of concessions. According to journalist Sebastian Strangio, the Government gave “Cambodian forests away to Thai and Malaysian logging firms and [kept] taxes low to maximize the informal profits that flowed back their way”. Cambodia’s forestry sector entered a period of “capitalist anarchy”.

In just two decades, Cambodia’s forest sector was utterly transformed, often at the cost of the poorest rural communities.

The change was rapid. From 1993 to 1995, 11 companies were granted forest concessions, totalling 2 million hectares. But by 1997, forest concessions covered all available production forest, totalling 6.5 million hectares, or around 65 percent of the national forest area. A year later, Strangio reported the World Bank estimate that “as much as 95 percent of the past year’s timber production had taken place off the books”.

The free-for-all nature of concessions and the high chance of short-term profits influenced how some villagers viewed their relationship with the land. “Villagers began to realize that because of the open market, there was now a price for land,” recalls Heng Thoin, community leader in Prey Thbong Domrey in Kampong Thom Province. “People started to pick up land and claim ownership.”

Whether it was smallholders or large-scale concessions, opportunities were largely limited to those with political or military connections. For researchers Jean-Christophe Diepart and Laura Schoenberger, this was a consequence of “massive and illicit land acquisitions” that led to the “de facto privatization of state resources” by provincial or district authorities, members of the military and police and other officials.

In just two decades, Cambodia’s forest sector was utterly transformed, often at the cost of the poorest rural communities. Yet, new models of forest management were emerging. While they generated much hope, they also faced many hurdles.