Speak to an expert in forest governance in the Mekong region and you will hear some words repeating: Implementation, participation, capacity, equity, monitoring and, of course, finance. They are among the gaps to fill. Ensuring that forests can work for people and for a stable climate depends, for example, not only on having strong laws and policies, but on implementing and enforcing them fairly and effectively. But forest governance is not just about how governments control and manage resources. It is also about how society can take part in decisions about forests and hold the powerful to account.

Julian Atkinson says we must ensure local civil society organizations have seat at the table and the capacity to meaningfully contribute. That means ensuring these groups have the capacity to network, share information, develop positions and take part effectively in decision-making structures and processes so they can advocate for their needs.

But it is not only civil society groups that need more capacity. The news media need to be able to cover forest governance issues better. The private sector needs support to understand and comply with policies and laws, while government officials have plenty to learn about effective approaches to policy development and legal reforms.

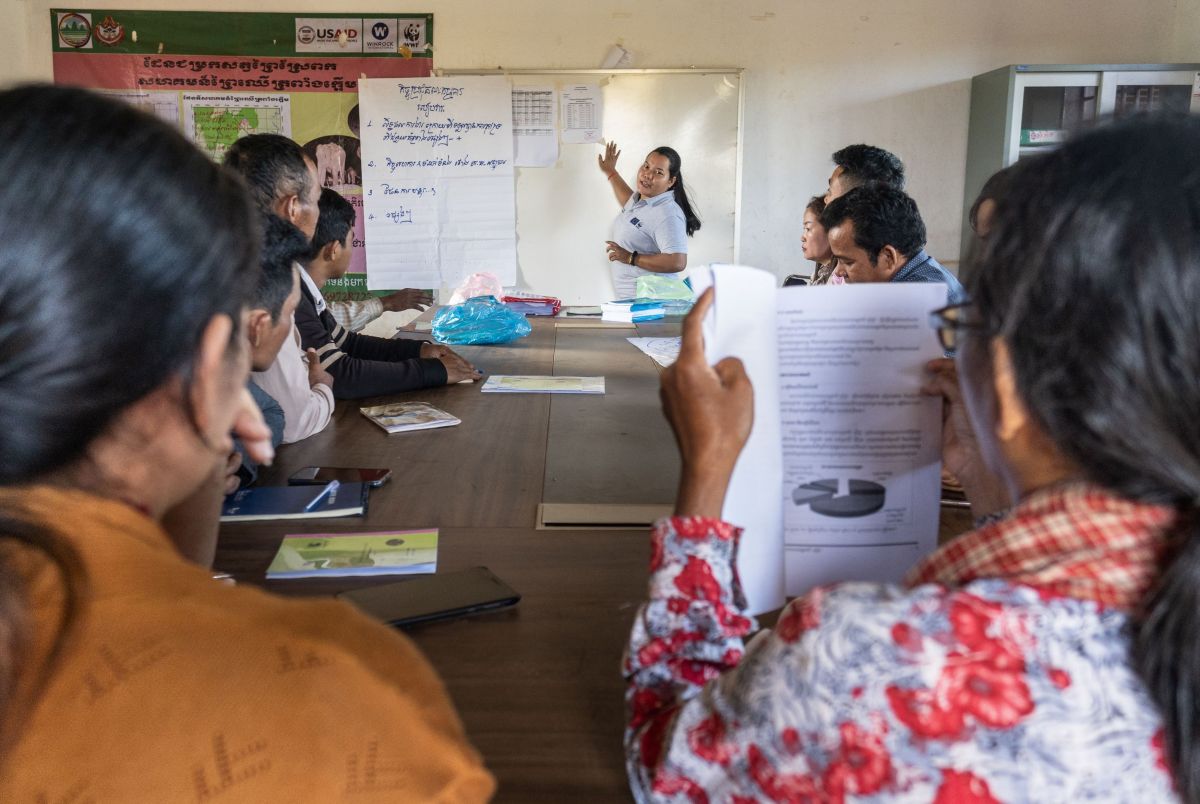

Much is happening to fill these gaps—from workshops and trainings to field trips and learning exchanges. Officials from Lao PDR have, for example, visited Indonesia and Liberia to learn about VPA implementation and to Mexico to learn about successful models of community forests.

Building capacity

RECOFTC, meanwhile, is building capacity among non-state actors with respect to facilitation and stakeholder engagement, community forest management, FLEGT VPA and REDD+ concepts and processes, addressing gender issues and free, prior and informed consent.

One important area for capacity development is in monitoring forest governance. In each of the five Mekong countries, RECOFTC is working with partner organizations to develop a participatory system for doing this.

“How do we foster change?” asks Atkinson. “It’s about having open access to, and sharing, information. It’s also about building the capacity of civil society organizations to use information.”

The team in Thailand has, for example, decided to develop an online portal to share information on forest governance issues, with a particular focus on REDD+ and the country’s Voluntary Partnership Agreement process with the EU. This is because non-state actors there say a lack of transparency and access to information limits their ability to monitor the state’s management of forests and to advocate for change.

"Even within the wider FLEGT vision, gender does not come out that visibly. The appetite is there, but there is lack of know-how about how to translate gender and social issues into the FLEGT context."

Kalpana Giri, Senior Program Officer, RECOFTC

RECOFTC’s executive director David Ganz says it is essential that governments in the region continue to listen to the voices of communities and civil society, and incorporate their views in policy. That means listening to a diversity of marginalized groups, especially Indigenous Peoples, youth, the elderly and women.

“There is a tendency to focus on the male voice,” he says.

One example of the gender gap is in the EU’s Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) Action Plan, says Kalpana Giri, who is part of the team implementing RECOFTC’s gender equity and social inclusion strategy.

“Even within the wider FLEGT vision, gender does not come out that visibly,” says Giri. “So it doesn’t come out in discussions so much, for example, when defining legality. FLEGT Voluntary Partnership Agreements were seen as economic trade deals, so they went in a technical, economic direction rather than social one. The appetite is there, but there is lack of know-how about how to translate gender and social issues into the FLEGT context.”

This matters because, while good forest governance is about moving forward in a positive direction, it is also about trying to ensure that no one is left behind. Experience shows, for example, that as countries root out illegality in their timber supply chains, they risk harming small and informal enterprises that struggle to keep pace with the changing rules and standards.

That’s why it is important to raise awareness among such businesses and build their capacity to participate in legal markets, says Vu Huu Than, RECOFTC’s Vietnam-based training coordinator.

Vu says governments could provide incentives and support them to register their businesses: “Small or informal enterprises should be encouraged to formalize. This will probably improve their performance and sustainability.”

In the balance

In the Mekong region, the fates of people and forests have been entwined for millennia. But as economies grow, pressure is mounting on the remaining forests and on the people who depend on them most. The coming decade will present risks and opportunities.

As the impacts of climate change become ever clearer, the case for protecting forests and managing them sustainably grows ever stronger. We must do this in ways that are fair and beneficial to local people, while also protecting biodiversity. And as the EU and other markets increasingly demand legal timber and commodities whose production has not entailed deforestation, the economic incentives for better forest governance should continue to grow. In 2019, for example, the EU launched an initiative to protect and restore the world’s forests (link), and the European Green Deal, which provides a basis for more action on forests (link).

There are challenges, of course, and some are deeply entrenched. But there are also examples of truly significant progress. By learning from each other, scaling up successful initiatives, continuing to involve all stakeholders in decision-making and building capacity, the Mekong countries can hope to balance economic development with forest protection. If they succeed, the whole world with benefit.