The 2017 June-September monsoon season in South Asia was one of the most devastating the region had experienced in decades. In Nepal, monsoon rains fell like a thick curtain for four days in August and the rivers swelled and broke their banks. Widespread flooding washed away roads and agricultural fields and forced hundreds of thousands of people from their homes. About one third of the country was flooded.

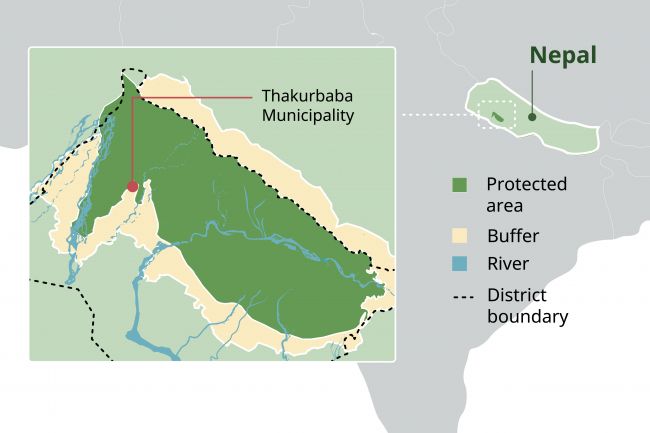

Thakurbaba municipality in Nepal’s south-western plains was among the worst hit areas. It was established by Nepal’s 2015 Constitution, which reorganized the country into seven provinces and 753 local-level bodies known as palikas. The Constitution mandates 22 exclusive powers to the palikas, including planning and implementation of local-level development.

The municipality conducted its first elections just a month before the August floods. After the initial rescue of victims, the new local government decided that it wanted a long-term vision for the future and a roadmap to get there.

“We wondered whether haphazard infrastructure development, deforestation and changing human behaviors contributed to the scale of damage,” says Thakurbaba’s new mayor Ghan Narayan Shrestha. “We thought that having a master plan would help us cope better in the future.“

Click any image to enter media gallery

New partnership develops a forward-looking plan

The plan had to take into account the town’s unique geographical location, especially its often strained relationship with the national park. The local people had no access to the park’s resources, and yet, they lived in constant fear of being attacked by wild animals from the park.

Shrestha’s municipal team reached out to officials from Care Nepal, a non-profit organization that had been partnering with the Hariyo Ban Program. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) program focuses on biodiversity conservation, and on building ecological and community resilience in the face of climate change.

“The municipality wanted a 20- to 25-year plan,” said Jagannath Joshi from Care Nepal. “We needed a partner who had a track record in forming long-term strategic plans.” That’s when they identified RECOFTC.

“We’ve been implementing many projects on forestry and securing community rights in Nepal and lobbying for municipal plans to include forestry,” says Shambhu Dangal, director of RECOFTC Nepal. “During workshops for community forests, we noticed a conflict between community groups and local governments due to limited coordination and collaboration. We realized that if we just talked about forests, the local governments would not listen to us. We needed to talk about local development while focusing on forests.”

In April 2018, the municipality team, RECOFTC and the Hariyo Ban Program agreed to work together. In a spirit of teamwork without any financial transactions, these independent organizations set to work preparing a guideline for Thakurbaba municipal government on how to develop a master plan.

Developing the municipal master plan

The process to develop the master plan was broken into two phases: pre-planning and planning. In the pre-planning phase, a planning team was formed and the municipality agreed on the process. In the planning phase, the team collected published data, conducted a rapid assessment on the needs and goals, and then assembled the required expertise. Finally, they moved through a few drafts of the master plan before reaching final endorsement. The entire process took six to nine months from inception to finalization.

Click any image to enter media gallery

About 100 people gathered for the planning. They included elected local representatives, social workers, health workers, teachers, farm representatives, hotel representatives and community elders. The first hurdle to overcome was to define the concept of ‘development’.

“We only saw development in terms of infrastructure,” says Shyam Lal Tharu, a local elected representative. “Like the rest of the community, the only thing that we wanted was a tarmac road.” Approximately 30 stakeholders from all nine local electoral subunits of the municipality worked for two weeks on a new definition of development: that basic needs are fulfilled and people can live with self-respect and freedom. Teachers were recruited to collect data from the population, estimated to be 55,000. The data collection team went house to house with a questionnaire. To make a holistic plan, the team had to ask difficult questions.

“We also had to find data about controversial issues such as Chhaupadi [ritual menstrual segregation] and illegal timber foraging from the park,” said Tharu. “That was challenging.”

Historical issues crop up

Deputy Mayor Krishna Kusma Tharu was not convinced about this process at the beginning. Deputy Mayor Tharu comes from the Tharu community, an indigenous community of Bardiya, displaced and enslaved by the migrants that the government had encouraged to settle here decades earlier. Growing up as a Kamaiya, a bonded labourer, Deputy Mayor Tharu had joined Nepal’s 10-year-long civil war between 1996 and 2006. The Kamaiya system was abolished in 2001.

With a background in radical politics, Deputy Mayor Tharu had dreams of radical change. Tasked with the job of promoting inclusion and resolving disputes, she soon realized that change is a slow process.

“I used to feel that I could bring about change in the municipality overnight,” she says. “It was only after I got elected that I understood that the bureaucrats who execute the programs and the elected representatives who plan development have to be on the same page.”

Aligning for a common vision

“Some of us face difficulties with wildlife, some with floods and others with education,” said Bina Bhattarai, a community organizer and a local representative. “In the process of discussion, we ended up with a common understanding.”

Even though wildlife attacks were frequent, victims had to wait a long time to be compensated by the National Park authorities. Locals who sustain injuries from wild animals often incur debts to receive treatment.

“We have to manage certain situations as soon as they happen,” says Nawaraj Dhungana, a local teacher and a social worker. “Urgent needs have to be addressed first and discussions can come later.”

As the process of planning placed a renewed priority on the well-being of people, the municipality decided to allocate its own funds for immediate relief.

“It’s probably the first time ever that any community has been involved in giving out relief like this,” says Bhattarai.

A unique document

The planning and the implementation of the strategic plan have brought people with diverse ideologies onto the same page. They have all agreed that development is about the well-being of people.

“After the restructuring of the nation, we are the first elected local body here,” says Mayor Shrestha. “We did not have an office building or land, nor did we know how to organize our working committee meetings or make policies.”

He and his team are proud of all they have accomplished in the past four years.

“We have endorsed 40 new policies. We have our own buildings as well as ward buildings. We’ve had regular annual assemblies. I’m very pleased with the process.”

Thakurbaba has been working on both infrastructure and social development while ensuring that the natural environment is respected.

In recognition of their work, the provincial government has allocated the municipality additional funding to implement its plans. The planning document is being used as a foundation by other municipalities across the country.

###

RECOFTC’s work is made possible with the support of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida).