Using innovative approaches to raise awareness on climate change in Indonesia

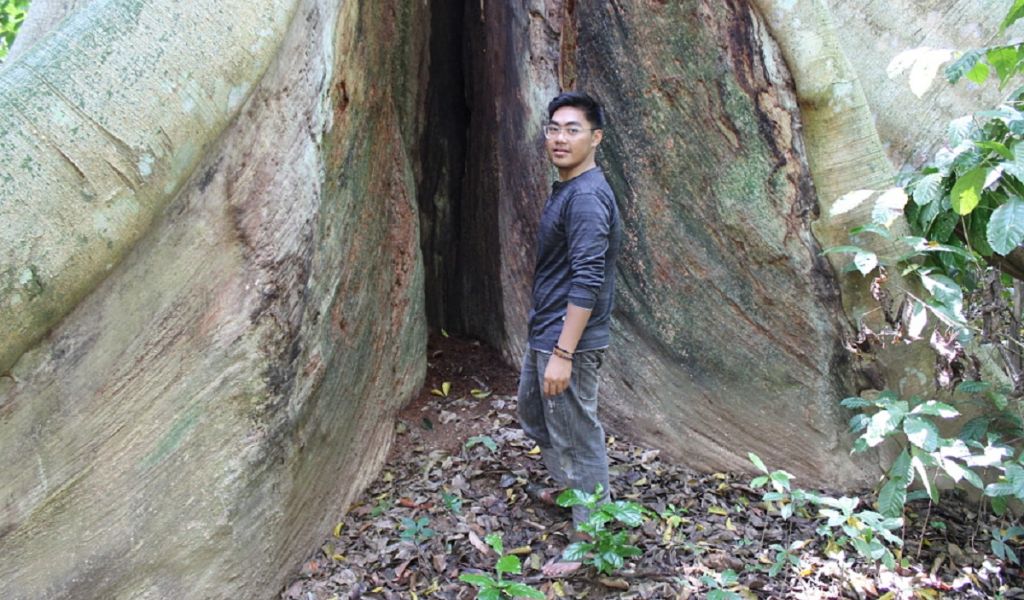

Born in a family of local home enterprenuer, Gilang grew up exploring the old city of Berau and Segah River and hiking the mountains of Berau District in Indonesia’s East Kalimantan Province. While conducting a research assignment in a remote village, Gilang trembled when he saw how lack of information and comprehension of climate change issues left local communities vulnerable to external pressure—specifically, conceding their lands to palm oil plantations.

To help educate villagers across the district, Gilang and a few friends started Yayasan Komunitas Belajar Indonesia (Foundation of Learning Community of Indonesia), or Yakobi. Their intent was to help the villagers understand changing climate conditions and develop confidence to speak up for their own interests so that over time they could manage their challenges without too much dependence on external support. Based in Berau and led by the now 26-year-old Gilang with a team of college graduates, Yakobi focused on educating villagers with a simple but uncommon approach. As a new organization, however, Gilang and his team soon realized that they lacked skills to implement their missions.

This quickly changed after Gilang attended RECOFTC’s facilitation trainings for climate change where he learned how to more effectively discuss climate change change issues using participatory approaches. Soon after, Yakobi became the local partner for RECOFTC’s Grassroots Capacity Building for REDD+ Project in Asia. Subsequently, other Yakobi team members also took part in capacity development opportunities that helped them in implementing the project activities.

First, they targeted four atypical types of leaders as education facilitators: tribal leaders, a government-supported women’s group members, religious leaders and school teachers. “These were groups of people who were rarely considered in project activities, but in fact, they could be very influential and likely more effective in spreading key messages to people at the grassroots level than us or other project staff,” Gilang explains.

Second, they stuck to formality and visited the necessary structural authorities repeatedly for authorization. “In the beginning, we had to regularly come to see the head of the offices or institutions at the regency or district levels to explain our project’s objectives and activities. Without their approval, we would not be able to hold any single activity. We had to constantly adjust our event dates to the leaders’ schedules,” he adds.

Third, when they met with targeted villagers to seek their approval for the proposed climate change education training, they had no arranged agenda. “When they first approached us in their earlier visits, they would come only to chat and get to know us—not bring up anything about the project,” explains Rosdiana, the member of the subdistrict women’s group who became a Yakobi facilitator in Biduk-Biduk village.

When they were finally ready to bring up climate change issues, they were perplexed. “The materials about climate change were usually very technical and packed with scientific jargon, which could not be easily understood by our grassroots audience,” recalls Gilang. RECOFTC guided the Yakobi team in simplifying materials and lesson plans and translating them into the local language.

The trainings involved countless visits by the committed team over six hours of travel on rugged terrain and carefully orchestrated phone calls. With electricity only available from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m., they needed to make appointments for phone calls. “I had to make sure that my cell phone was fully charged the night before and get on my motorcycle to go to a hotspot where I could call or receive calls at agreed times,” recalls Rosdiana. “They were always available to answer my questions and willing to support me.”

Rosdiana admits that before the training she was not aware of climate change nor had the confidence to talk in a meeting. “The methods used in Yakobi’s training were very simple and inclusive. As participants, we were always encouraged to actively take part in discussions and do presentations. This built not only my knowledge on climate change but also my confidence,” she says.

Fifth grade teacher Agus Uriansyah, who is a Yakobi facilitator in his school, found Yakobi’s approach a learning process transformation for both him and his students. Previously, he explains, climate change was only part of a module in the science lesson. That changed with Yakobi’s trainings. “I learned how to design lesson plans so the students would be interested and excited to learn. I even felt encouraged to create my own teaching aid materials and activities. It was amazing to see how quickly the students understood the concept of climate change and its impact on our environment,” he says.

Using the knowledge on climate change gained from Yakobi’s training to facilitate decision-making in his community brought personal gratification to Zulfikri. As a teacher and religious leader, he constantly reminds the community of the consequences of not looking after the environment. “Our beloved God has warned us in the holy book of what we would reap from the actions of our hands. We should not be tempted by short-term gains while we have generations to come that need feeding,” he tells them.

“Our dream is to foster local facilitators at the grassroots level, particularly in remote areas, as much as possible and support their capacity development so they could respond to the need for knowledge and technical capacity in the community by themselves."

When several villages were invited to discuss palm oil concession plans, Zulfikri did not hesitate to voice his objections. “I shared my opinions to my community and, as a result, we decided to reject the offer to convert our forests to be a plantation, even though our village head was in favour of the scheme,” he says.

As a result, he points out, “We still have our forests and have no problem with water and crops—unlike the other villages who agreed to the scheme.”

Listening to the positive feedback and comments, Gilang feels proud but quickly assures that there are much more to be done. “Our dream is to foster local facilitators at the grassroots level, particularly in remote areas, as much as possible and support their capacity development so they could respond to the need for knowledge and technical capacity in the community by themselves. With that capacity and confidence, we are confident they could protect and manage their own resources instead of succumb to being the objects of research and shadowed by NGOs.”