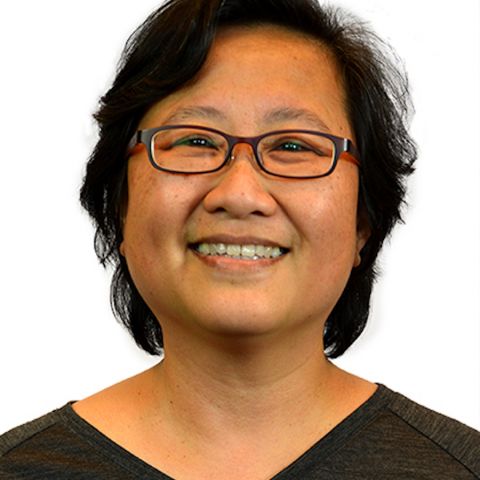

"Governments in Southeast Asia are changing how they think about forests and the people who depend on them, and are increasingly open to discussing topics that until recently were considered ‘too sensitive’ ", says social scientist and natural resources expert Grace Wong.

The Malaysian researcher, based at the Stockholm Resilience Centre in Sweden, says the growing openness to consider issues of social equity in the forestry sector is just one of the significant outcomes of a 10-year collaboration between the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and Switzerland.

The ASEAN-Swiss Partnership on Social Forestry and Climate Change (ASFCC) was formed in 2011 to help ASEAN and its Member States develop, reform and implement policies on ‘social forestry’, enabling communities to manage and benefit from local forest resources. By 2020, ASEAN countries had doubled the area under this form of community forestry.

Along the way, the ASFCC changed many minds.

Wong says, for example, that governments previously rejected the possibility that traditional shifting cultivation could have a role to play in sustainable forestry, instead outlawing the practice. But having seen and understood research on the topic, policymakers began to change their minds.

Wong, who led some of that research while working at the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), says: “It moved from ‘We don’t want to hear about these guys. It’s all illegal’ to ‘Okay. There are lessons we can integrate and how we can make social forestry a more equitable process for different groups’.”

In this article, Wong and six other experts reflect on the progress the ASFCC made, and share thoughts on how to ensure social forestry can meet its true potential.

Big challenges the ASFCC tried to tackle

Southeast Asia experienced rapid deforestation in the past century, and many of its most important forests are today being rapidly degraded or cleared to make way for agriculture. But while this has brought economic gains for countries and big businesses, it has created conflict with local communities that depend on forests for their lives and livelihoods. Part of the problem is that forest communities often lack secure tenure and rights to use forest resources.

At the same time, forests have key roles to play in efforts to protect biodiversity and limit climate change. But sustainable forest management remains elusive, and governments lack the capacity to stop forest crimes and prevent forest degradation.

The ASFCC set out to help ASEAN and its Member States to address all these challenges by harnessing the potential of social forestry to create sustainable livelihoods, reduce poverty, improve food security and contribute to climate goals.

Social forestry is based on the idea that when communities are allowed to protect, manage and benefit from local forest resources, they will manage those resources sustainably. But there is no one-size-fits-all approach. Contexts vary within and among countries. Legal frameworks, forest types, agricultural systems, customary governance practices, knowledge, skills and resources all differ from place to place. This poses challenges to both national and regional policy processes that aim to promote social forestry.

Making the case for social forestry

Suriyan Vichitlekarn was Senior Officer and later Head of the ASEAN Secretariat’s Food, Agriculture and Forestry Division from 2008 to 2013. He saw the early impacts of the ASFCC. He says that, before the ASFCC, there was no common understanding in ASEAN of what ‘social forestry’ is, how it contributes and how it relates to the ASEAN agenda.

“So, the first important point was creating common understanding and trying to put everything under one single roof, of course with understanding of national differences and contexts,” he says.

The ASFCC was designed to support the ASEAN Working Group of Social Forestry (AWG-SF), which gathers officials from ASEAN Member States to promote social forestry policies and practices. It did this through the work of five implementing partners: RECOFTC, the World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF), the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), the Non-Timber Forest Products-Exchange Programme (NTFP-EP) and the Southeast Asian Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture (SEARCA).

“ASEAN is good at setting policy but weak in implementation,” says Vichitlekarn. “To tap into the expertise of regional institutions and agencies, such as RECOFTC and so on, we recognized some collaborating partners and for the first time ASEAN policy implementation in the forestry sector was not confined only to public agencies.”

These groups did research, provided policy advice and training, funded pilot projects, organized learning exchanges, and supported deliberation among forest stakeholders from governments, civil society organizations, the private sector and communities.

“The ASFCC’s pilot projects and other activities have highlighted the importance and contribution of social forestry to rural and Indigenous Peoples, sustainable forest management and addressing the impacts of climate change,” says Vichitlekarn.

He also praises the structure of the ASFCC and its link with the AWG-SF, which enabled policymakers, researchers and civil society organizations to discuss issues related to the forest sector as never before.

Fostering dialogue, shaping policy

“The mechanism of engagement was an important foundation because, historically, ASEAN tended to focus more on engagement of governments, of public agency representatives, in setting policy, in laying down cooperation frameworks, in terms of defining what should be the impacts and results,” says Vichitlekarn.

“This is often a translation of national common policy interests into a regional framework,” he says. “But we often see the limitations of how this is perceived by other stakeholders. The ASFCC initiated a process to engage civil society organizations. So, for the first time civil society organizations had space in the consultation on the forestry sector at the ASEAN level.”

As the partnership went on, the AWG-SF began to produce policy documents. With ASFCC support, it developed the ASEAN Guidelines for Agroforestry Development and contributed to the development of the ASEAN Multisectoral Framework on Climate Change, Agriculture and Forestry towards Food Security.

“Through this very focused entry point, this ‘social forestry window’, the ASFCC quite significantly supported the regional dialogue, not only in forestry but beyond forestry as well,” says Dian Sukmajaya, Senior Officer in the Food, Agriculture and Forestry Division of the ASEAN Secretariat. “The ASEAN guidelines for agroforestry development have been adopted by all countries and some countries are now developing their national agroforestry roadmap.”

The ASFCC partners also contributed to legal and regulatory reform processes in individual ASEAN member states. Ricky Alisky Martin, a government officer in Malaysia’s Sabah Forestry Department has been involved in ASFCC activities since 2013. He says: “To Malaysia, the most important achievement is that ASFCC assisted us in developing the National Social Forestry Roadmap, which is a strategic action plan on social forestry for the years 2021 to 2025. We have also produced our national vision of, mission on and definition of social forestry.”

New urgency, old challenges

Thanks to new laws and policies introduced by ASEAN Member States, the total area of social forestry more than doubled between 2010 and 2020, to 13.8 million hectares. And if Member States reach their targets for 2030, local communities will manage a combined area of more than 30 million hectares. That would be nearly a 500 percent increase since 2010.

But since the ASFCC began in 2011, much has changed. Asian economies have been growing, but so has inequality. Deforestation continues as demand for commodities grows. Meanwhile, global greenhouse gas emissions have continued to rise, making the need to address climate change ever more urgent. And most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has hammered livelihoods, increased pressure on natural resources for subsistence and provided cover for an increase in illegal logging.

There are opportunities too. The pandemic has created an unprecedented chance to reshape the way economies affect the environment. Amid growing calls for a ‘green post-Covid recovery’ that prioritizes sustainable livelihoods, climate action and nature restoration, the arguments for social forestry grow stronger.

But against this backdrop of risk, uncertainty and opportunity, entrenched challenges continue to hold social forestry back from achieving its potential. Governments lack personnel and resources dedicated to social forestry. They need to better coordinate action among the different sectors that social forestry affects, and improve data sharing, says Bounpone Sengthong, the Deputy Director-General of the Department of Forestry in Lao PDR.

He points out that communities also need considerable support, including from extension services, if they are to succeed at social forestry.

“We have quite a large number of forest management plans at the village level,” says Sengthong. “But how to get the villagers to do their work, like forest restoration, forest management? There is still a lack of support.”

"We have to focus a little bit less on targets and more on the care of how these things are being implemented, and what it means for people on the ground."

Grace Wong

Other challenges relate to the rights and responsibilities of communities that engage in social forestry. Grace Wong highlights weak tenure and resource rights.

“Whether it is payments for ecosystem services or community forestry, it is the state setting rules which means that they have control over the forests despite it being somewhat devolved,” says Wong. “In a lot of the cases in our research, communities are doing the work of forest management without the recognition of their rights to the resource."

Countries need to allocate more and better-quality forestland to communities, says Yurdi Yasmi, who led the formation of what became the ASFCC while working at RECOFTC. He is now the International Rice Research Institute’s Regional Representative for Southeast Asia.

“Social forestry is often implemented in highly degraded forests where government partners with a community to do rehabilitation, so the actual benefit going back to the people, to the poor people, could be limited,” says Yasmi.

And in some countries, he adds, benefits are further limited by laws that prevent communities from selling timber harvested from forest land they manage.

“This is the main issue: Social forestry cannot touch the most valuable resources in forests, which are good trees, because governments do not trust local communities to manage rich forests.”

Promoting entrepreneurship

Yasmi says that, to unlock the potential of social forestry, governments will need to trust communities more, allowing them to operate commercially and supporting their entrepreneurship. For this to happen, he says, communities will need secure tenure rights, rights to commercialize, adequate legal frameworks to support such enterprises to develop, and capacity to manage forest resources sustainably and engage in value chains for forest products and services.

“If you open local communities to markets, they are very creative,” says Yurdi. “If you provide them with information on how to design products consistently, how to target specific markets, or niche markets for certain products, then they will benefit. We really have to do this entrepreneurship at scale. When you put money into the pockets of the local community, they will be happy. They will conserve your forest.”

Scaling up social forestry and supporting villagers to manage, produce and market forest resources will require considerable funds. The experts interviewed here see opportunities to attract finance by linking to forest landscape restoration initiatives and to forest carbon markets through REDD+, the initiative aimed at mitigating climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions from the forest sector.

“REDD+ is still the instrument with most momentum globally for forests,” says Keith Anderson, the Senior Advisor for international forest policy at the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment. “It should be closely articulated with community-based forestry, with scope for a large range of types of business and for adding resilience, securing forest ecosystem services and increasing agricultural production.”

Anderson suggests adding value to conservation areas by developing eco-tourism, supporting community-based small- and medium-sized enterprises and selecting high-value plants for farmers to grow. This, he says, would counter arguments for replacing forests with monoculture and would build resilience to market downturns and climatic risks.

Anderson also says social forestry should “get out of the silo of just forestry” or risk missing out on opportunities created by the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, the Bonn Challenge and increased private-sector interest in landscapes.

“Forests only gain in relevance when linked to landscape management and landscape restoration,” he says.

Changing mindsets

Suriyan Vichitlekarn also wants more people to understand that even though the term ‘social forestry’ has ‘forestry’ in it, it is not mainly about forestry. It is about people. He says this would allow for other sectors to recognize the potential contribution of social forestry, in terms of strengthening rural employment, improving livelihoods and addressing the needs of Indigenous Peoples.

For Yurdi Yasmi, one of the key missing ingredients is trust.

“Communities have been saving our forests,” he says. “Governments have to know that without communities they cannot manage the forests. You look at Brazil, Congo Basin, Indonesia, Viet Nam, once you deal with companies, they destroy your forests. But you look at these communities—when you trust them, they conserve forests. So, we have evidence. We have to shift mindsets on this.”

But Grace Wong warns that rushing to implement social forestry without taking time to see how it fits into local contexts can create in some cases more problems than it solves.

“ASEAN countries are not always very responsive in terms of social and human rights,” says Wong. “They may be more concerned about pushing an economic agenda or a growth agenda, so social forestry risks being lost within these kinds of political agendas. We have to focus a little bit less on targets and more on the care of how these things are being implemented, and what it means for people on the ground.”

“Social forestry is sometimes a little bit of a straitjacket, with very structured models, very bureaucratic rules,” says Wong. She says it is important to monitor and assess the impacts of social forestry, and not only in economic terms but also with respect to rights, agency and making sure different social groups are included.

“I try to push monitoring, accountability and diverse voices to make sure that we may get a social forestry that hopefully meets its ideals,” she says.

###

RECOFTC’s work is made possible with the support of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida).